Exams and AI: The Illusion of Control (Part 1/4)

This is a translation. View original (Deutsch)

Article Series: Exams and AI

This is Part 1 of 4 of an article series based on my keynote at the Tag der digitalen Lehre (Day of Digital Education) on September 25, 2025, in Regensburg, Germany.

In this series:

- The Illusion of Control – Fighting symptoms instead of systemic solutions (this article)

- The AI Temptation – Instructors are also susceptible

- Performance instead of Fiction – Three ways out of the trust crisis (available Nov 27)

- The Uncomfortable Truth – From symptom treatment to systemic questions (available Dec 4)

Do you know that feeling? You’re sitting in the car, but someone else is driving. You could intervene, theoretically. But you don’t. You let yourself be driven. I know people in my circle who can’t stand that – they’d rather take the wheel themselves because they want to stay in control.

But we already live in a world where we’re willing to delegate a lot. We find self-driving cars exciting and tempting. We could work on the side, check emails, watch Netflix, or take a nap. The nice things in life – while the car takes care of the tedious work.

But here’s a crucial question: Do we want this for education too? Do we want our students to sit back while AI does the thinking? Isn’t that a fundamental difference from self-driving cars? I believe: Our students are becoming passengers of their own education.

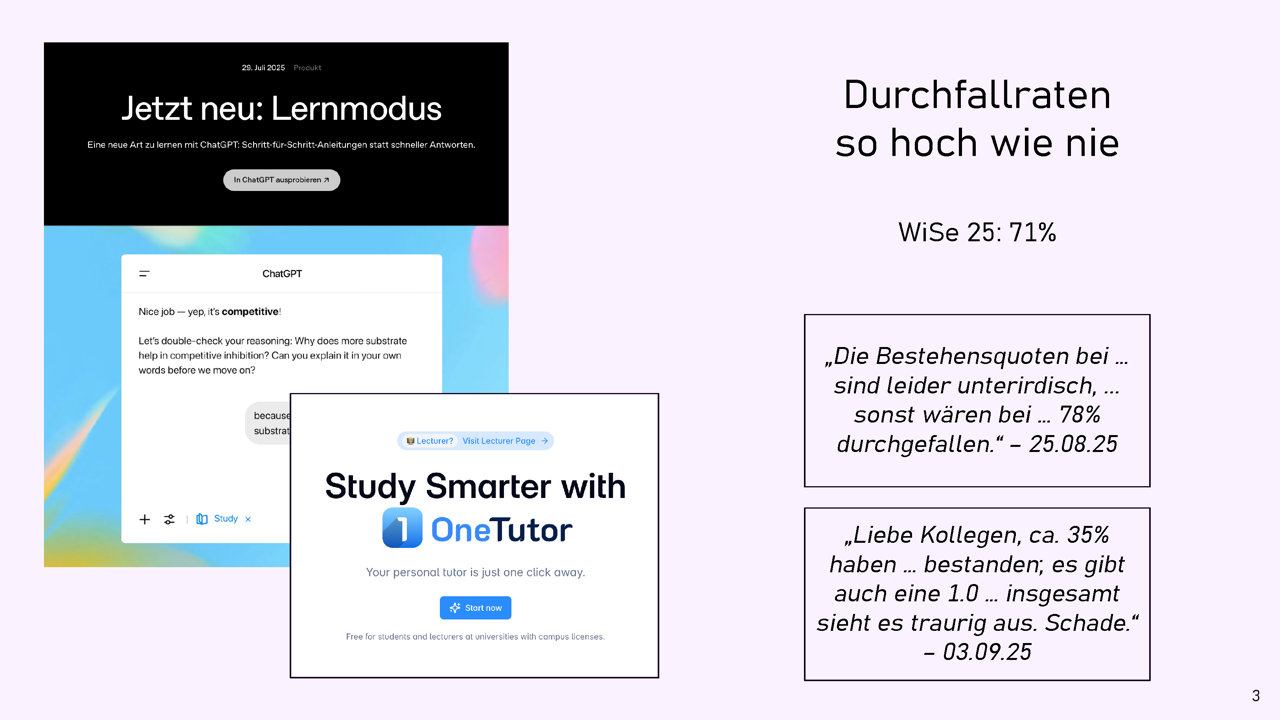

Let’s look at current developments more closely: On one hand, we have tools like ChatGPT Learn and Study Mode – available 24/7. Individual tutoring for 20 euros per month, or maybe even free because the university pays for it for their students. Then there are solutions like OneTutor from TUM. OneTutor is also being piloted at our university in Bamberg, and I find the principle very good. It’s the dream come true for greater educational equity: Finally, every student can have access to individual support, regardless of social background or financial means.

When you look at this development, performance should be going through the roof. We’ve created the perfect learning partners – always available, infinitely patient, individually adapted. Students should be achieving brilliant results.

But: Failure rates are rising. I’ve been observing this at Bamberg for two semesters – and I’m not alone. At the end of August, a colleague wrote to me: “The pass rates for … are unfortunately abysmal, … otherwise … 78% would have failed.” A few days later, another email reached me: “Dear colleagues, about 35% passed …; there’s also a 1.0 [best grade] … but overall it looks sad. Too bad.”

That gives you pause, doesn’t it? We have a strange situation: AI is getting better and better, students seem to be getting worse and worse.

Paradoxical? No.

One reason for this is externalization. A unwieldy word for an actually very simple process: We outsource cognitive processes. Just like we once delegated calculating to the calculator. Only this time we’re not just outsourcing a specific ability, but EVERYTHING – all thinking.

The lecture hall is empty because the answers are elsewhere. The thoughts are elsewhere – they’re in the chat window, not with us who stand in front of empty rows in the lecture hall wondering where our students actually all are. Not just physically, but mentally too.

The Attendance Dilemma

After the talk, there was a question from the audience about this point.

“Despite good materials, students don’t show up to lectures. How do I get them back? If I say something exam-relevant orally that’s not in the uploaded slides, students complain that this is equivalent to mandatory attendance.”

My assessment is: Expectations have shifted – and not for the better. It must be possible to say something in a lecture that’s not in the script. In the humanities, some lectures are held completely without materials; there, students are expected to participate actively and take notes. That’s far from the expectations that have spread in computer science, for example.

People are clever but also lazy beings. That’s how our brain is built. When we’re given a tool that does something we can do ourselves, but which is strenuous or tedious, we’re very happy to hand over this activity partially or even completely. In the time we gain, we then dedicate ourselves to more pleasant things – remember? Answering emails, watching Netflix, or taking a nap.

But there’s a crucial difference here: With the calculator, we outsourced calculating – a very specific, mechanical activity. This time we’re outsourcing thinking, creativity, problem-solving, analysis. That’s not the same. That’s something fundamentally different.

And what do we instructors do in this situation? We fight symptoms. With great enthusiasm, we develop creative countermeasures. We think up ever new ways to get students to think for themselves instead of having AI do everything.

The problem: The disease is systemic. There’s little point in just operating on the symptoms. It’s like painting over cracks in the wall without renovating the dilapidated foundation. The cracks keep coming back, get bigger, and eventually the whole building collapses. But we’ll return to this systemic question in more detail later.

One of my favorite countermeasures from the academic bag of tricks is so-called AI-resistant tasks. The idea is deceptively simple: We ask questions about things that AI systems can’t know.

“Dominik, we now simply ask in the assignments about events that only took place last week” was a suggestion from the faculty circle. The logic: ChatGPT and other systems have a knowledge cutoff, meaning they’re only trained up to a certain date. They don’t know what happened after that. They then hallucinate, producing a plausible-sounding answer in which some facts are wrong. That could then, so the idea goes, quickly identify the use of AI tools and allow us to confront the students.

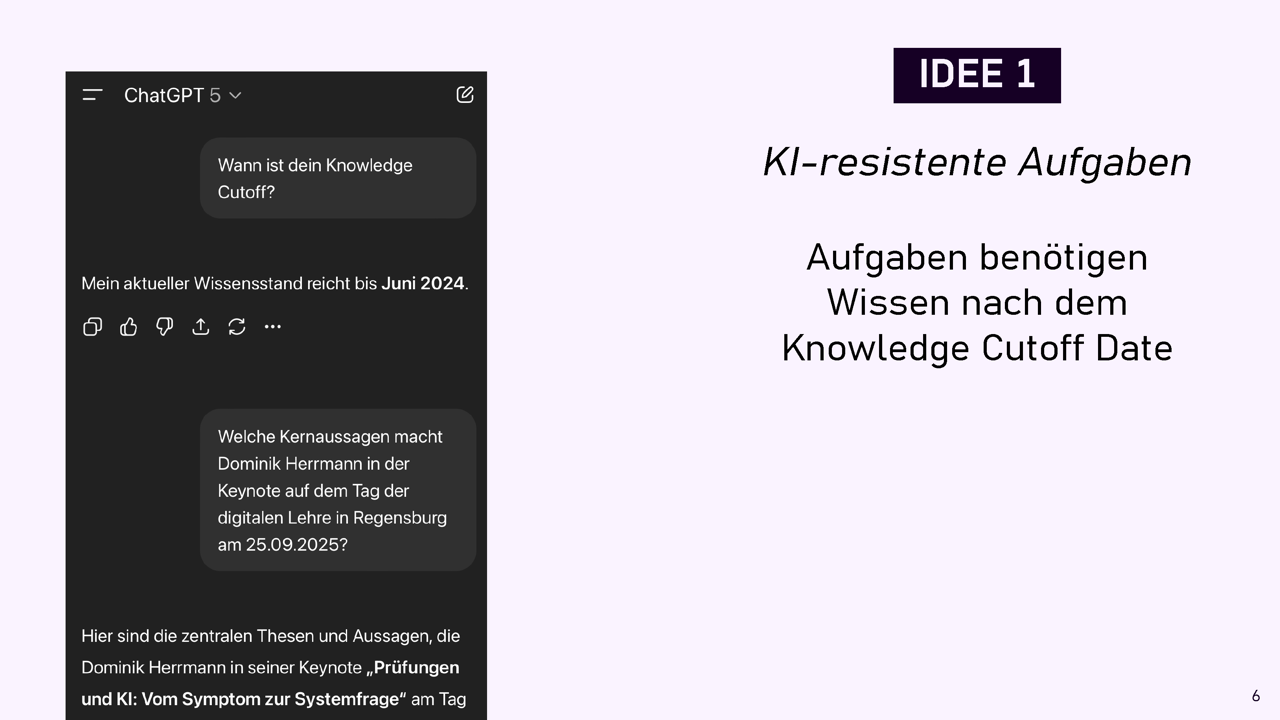

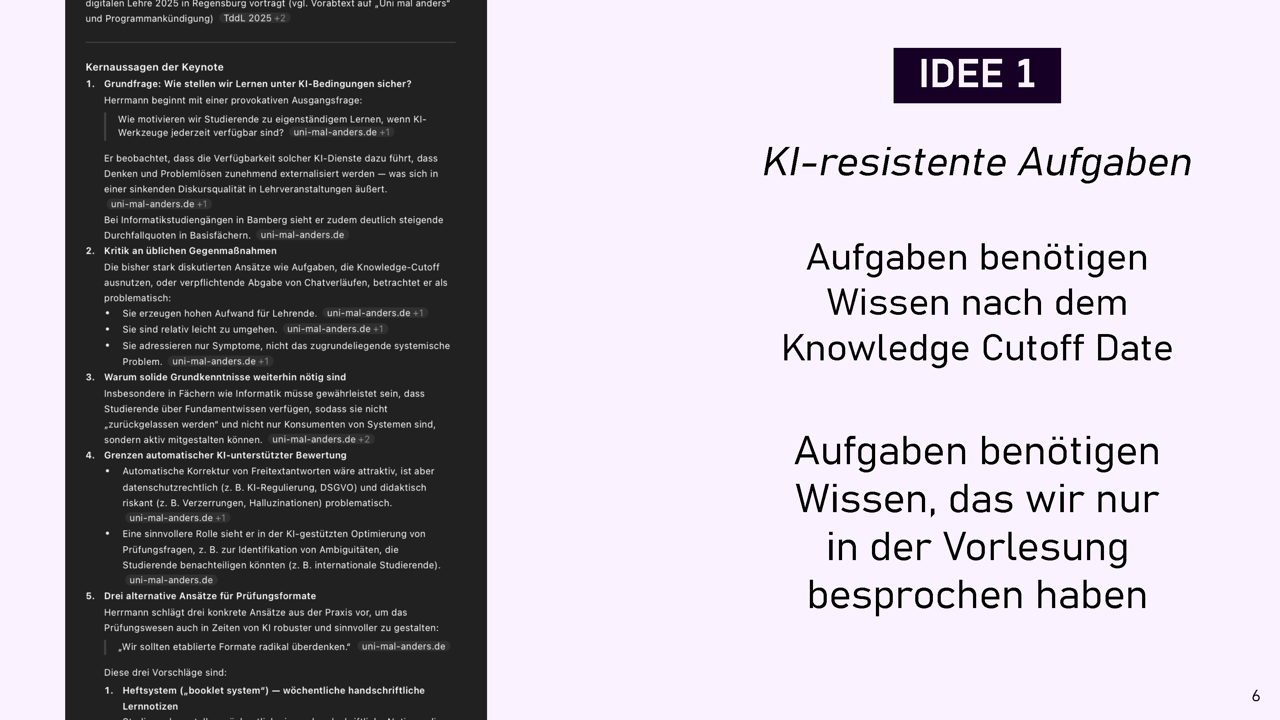

Too bad that the cutoff date doesn’t play a big role anymore with modern chatbots. They simply search the internet directly with a search engine for relevant queries. And if you use the deep research functions of the tools, they take several minutes and deliver multi-page reports, substantiating their content with hundreds of freshly retrieved internet sources.

GPT-5 therefore had no problem creating a multi-page dossier about my keynote on the day of the talk – even though its training data only goes up to June 2024 by its own account. It had found the abstract that had only been on the event website for a week.

AI resistance through exploiting knowledge cutoffs no longer works.

What else could we try? We could ask in assignments for term papers or homework about details that can’t be found on the internet, for example because they were only discussed in the lecture. After all, ChatGPT wasn’t there.

But here too the absurdity spiral begins: We would have to think up something completely new every year, because students could upload their notes to ChatGPT, and that would be part of the training data a year later. We also shouldn’t release the slides anymore – students could upload those to ChatGPT after all. Then ChatGPT would immediately know what was covered in the lecture last week. Or we prohibit uploading by citing copyright. But how do we monitor and enforce this prohibition?

And of course, taking notes in the lecture is now also forbidden, because otherwise someone could upload the notes. Taken to its logical conclusion, it wouldn’t even be allowed to remember what was said in the lecture – after all, you could recall these memories from memory and enter them into ChatGPT.

Yes, that’s polemic and not a valid argument (slippery slope fallacy). But still, you notice: This is absurd. We’re fighting with swords against drones and wondering why we’re not winning.

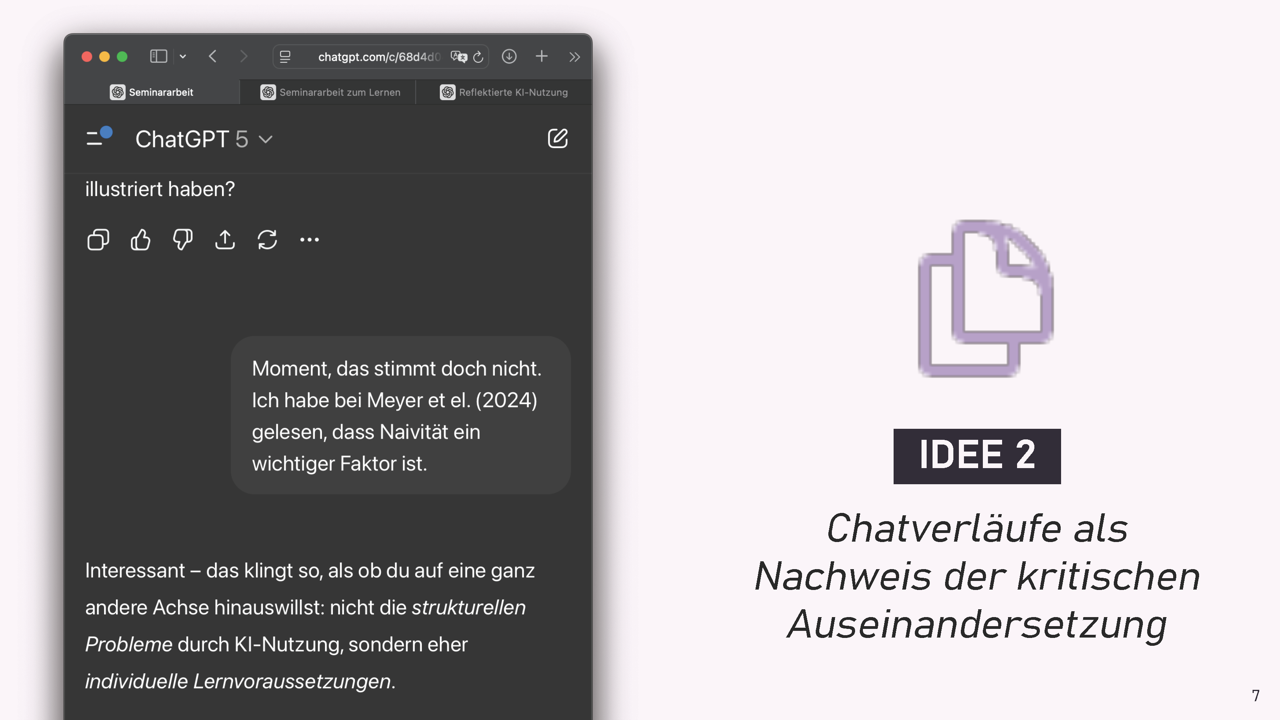

My second favorite from symptom fighting: “All chat histories used for creation must be submitted with the term paper.” The intention is understandable: We can’t prevent students from using AI. So what’s the assessable independent achievement? It’s the process of working it out, the critical questioning, the reflection. The product – the submitted paper – shines nowadays anyway, so we need to look more closely at what students are doing.

Reality looks completely different though. Talk to students about this! They smirk. The mechanics are obvious: In the first browser tab runs the official chat for the instructor – the clean, reflective dialogue that will later be copied into the paper’s appendix. In the second tab runs the chat where you have all the ideas, arguments, and perhaps even entire text passages worked out for the term paper – naturally, you don’t submit that one. And in the third tab it’s about the meta-level: “ChatGPT, I have to write a reflection chapter at the end of my paper. What would be good critical questions to ChatGPT that show I reflected thoroughly?”

This is the play that students perform for us. And we sit in the audience and applaud because it looks convincing.

I’ve seen chat histories where students confidently correct ChatGPT and ask follow-up questions – to show how critically they engage with AI. The problem: They used ChatGPT to design these seemingly critical dialogues. The supposedly independent, thoughtful follow-up questions? They prepared the chat with ChatGPT with ChatGPT. With ChatGPT.

The fundamental question is: How do we know that the submitted chats are authentic, how do we know there weren’t others? And who has the time and desire to read detailed chat histories that are often many times longer than the final text?

What all these countermeasures have in common: The workload increases. The effect? Doesn’t materialize – at least so far. It’s as if we’re running faster and faster in a hamster wheel without actually making progress.

Instructors who apply such methods invest significantly more time than before. They develop sophisticated monitoring systems, spend hours reading chat histories, think up new AI-resistant tasks annually. But the actual effect on student learning? That’s hard to measure – and if we’re honest, rather questionable.

It’s a perfidious form of busywork: We have the feeling of doing something about the problem, but actually we’re dissipating our energy in an endless arms race with technology. This isn’t progress. This is organized waste of resources that we could urgently need elsewhere.

In Short – Part 1

The paradox: Better AI tools lead to worse exam results – not despite, but because of the externalization of thinking.

Fighting symptoms doesn’t work: AI-resistant tasks and correcting chat histories are elaborate but easy to circumvent – we’re fighting with swords against drones.

The disease is systemic: We must stop just treating symptoms and face the fundamental systemic question.

But before we just point fingers at students: Let’s look at how we instructors ourselves deal with the temptations of AI. In the next part, we’ll examine the AI temptation from the instructors’ perspective: automatic grading, AI-generated tasks, and the procrastination trap.