Zero-Trust Vision: TEARS and the Future of Anonymous Examinations (Part 4/4)

This is a translation. View original (Deutsch)

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

In this 4th part we show how far one could drive the data protection idea: TEARS – a zero-trust system with paper slips that proves genuine anonymity in examinations is technically possible.

Previously published:

To conclude our series, we show how far one could drive the data protection idea: TEARS – a zero-trust system with paper slips that proves genuine anonymity in examinations is technically possible.

TEARS: Zero-Trust Grading

Let’s come to the last part, which is more academically interesting. It’s about showing how far one could drive the data protection idea. On my slide about goal conflicts, two points are still open: anonymous grading and power imbalance.

I had already hinted at the structural problem: Students find themselves in an ungrateful situation. They are at the mercy of what the university as an institution and we as examiners specify. However, it would be desirable if both parties could act on equal footing in the examination situation – after all, it’s about the students’ future.

Therefore, a provably anonymous grading would be desirable. This would mean that nobody has to rely on the goodwill or integrity of the university.

With our psi-exam system – and all e-examination systems I know that are used in practice – students must trust the university. After the exam, the answers are downloaded from the laptops by the organizer. The answers still bear the names of the test-takers at this point. Only when the data is passed on to the examiners are the names replaced by animal pseudonyms.

This mechanism presupposes that the organizer keeps their promise – i.e., doesn’t send the examiner an invitation link that reveals the actual names before completion of grading. Perhaps examiner and organizer are colleagues who work together a lot – how credible is such a promise then? If you often have lunch together or sit together at after-work drinks?

And what do we do when both roles – as with me currently – are united in one person? Then I’ll probably have to compartmentalize my thoughts better in the future… This is unsatisfying and hard to maintain in practice.

One could now retreat to the position that organizationally enforced role separation suffices – it’s simply regulated by service instruction and then everyone will certainly stick to it!

But wouldn’t it be more elegant if we could solve this technically so that no trust is necessary? It would be particularly elegant if we could solve it so that even technical laypeople could understand that the procedure establishes anonymity. One should be able to understand it without knowing how the cryptographic procedures usually required for this work.

This is a nice problem.

Anonymity Through Tearing

We have developed an elegant solution for this problem. It’s called TEARS – from the English “to tear.” The basic idea: Paper tears unpredictably.

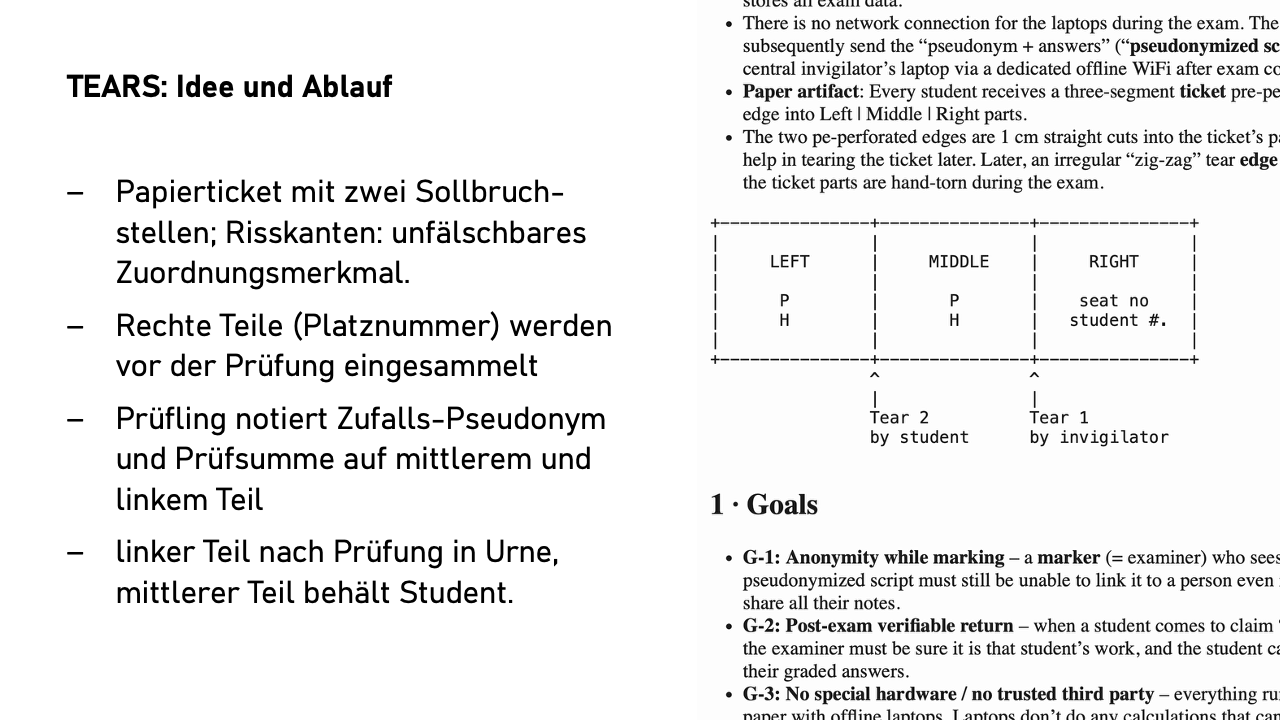

Each test-taker receives a paper ticket with two predetermined breaking points that is torn into three parts during the exam. The irregular tear edges are practically unforgeable. It is impossible in practice to perfectly replicate a tear edge created during the exam at home.

At the beginning, the supervisor comes to each seat, tears off the right part of the ticket, and notes the name and seat number of the student on it. The supervisor keeps this right part – it has a tear edge that will later fit perfectly with the middle part.

At the start of the exam, each laptop shows a randomly generated pseudonym – let’s say “A37BTX.” The student writes this pseudonym on both the middle and left parts of their own ticket. Then they work normally on the exam. Test-takers do not enter their name on the laptop.

At the end of the exam, the system shows a checksum over all entered answers – a kind of digital fingerprint of the exam. The student also notes this – let’s say, ten-character – string on both remaining parts. The left part is torn off when leaving the room and thrown into an urn – a box where all left parts land unsorted. The student takes the middle part home. This part is the crucial piece of evidence – it has both tear edges and can later be matched with both the right part (with the supervisor, after the exam with the examiner) and the left part (in the urn, after the exam also with the examiner).

Grading is done completely anonymously under the pseudonym. Examiners only see “Exam A37BTX” with the corresponding answers.

For grade announcement, the student brings the middle part and says: “I am Max Müller, here is my ID.” The examiner fetches the other two parts – the right one with “Max Müller, Seat 17” and the left part matching the middle part – easily found by pseudonym and checksum – from the urn. Now comes the puzzle game: Only if all three tear edges fit together perfectly is the assignment proven and the performance is announced and recorded for the student.

Is This Secure and Anonymous?

Security lies in the distribution of knowledge. Even if all parties worked together, they would always be missing a crucial puzzle piece.

The supervisor knows the right parts with the names and sees the left parts in the urn with the pseudonyms. But which left part belongs to which right one? This cannot be determined – the connecting middle piece is missing.

The examiners in turn only know pseudonyms and the associated examination answers, but no names. The only connection between all three parts is the middle part with its two matching tear edges – and only the students have that.

One could now object: What about forged tear edges, perhaps to get the better grade of other students? Here physics comes into play. The supervisor tears the ticket spontaneously and without preparation – simply as it comes. This random, irregular tear edge is unique. You could try at home a hundred times to replicate exactly this pattern – it will hardly succeed. And even if: The middle piece needs another perfectly matching edge to the left piece on the other side. So that has to tear perfectly again – and you only have one attempt for that – in the end, the three parts must again have exactly the format of the original ticket.

This elegant solution naturally has a catch: What happens when students lose their middle part?

If only one person loses their middle piece, that’s not yet a problem. After assigning all others, exactly one exam remains – problem solved. It becomes critical when several students lose their papers. Then theoretically any of the remaining exams could belong to any of them.

The system therefore needs a backup procedure for such cases. But here it gets tricky: The backup must not undermine anonymity, otherwise dissatisfied students would have an incentive to accidentally lose their papers to benefit from the exception rule.

We haven’t yet come up with a really convincing backup procedure. If someone has a good idea – I’m all ears!

TEARS is a thought experiment that shows: Data protection through technology can go much further than most think possible. You don’t need blockchain, no zero-knowledge proofs, no highly complex cryptography. Sometimes the analog solution is the more elegant one.

Will we implement TEARS practically? Probably not. The danger of lost papers, the organizational effort – much speaks against it.

But that’s not the point either. TEARS shows that genuine anonymity in examinations is technically possible. If a zero-trust system works with paper slips, then the argument “that just doesn’t work (better)” becomes less convincing. Often it will certainly be used as a pretext; what’s actually meant is: “We don’t want that.” That’s perfectly fine – but we should be honest about what’s technically possible and what we don’t want to implement for pragmatic reasons.

Conclusion: Where Do We Stand?

We have played through two goal conflicts here: data protection versus AI benefits, anonymity versus control. The perfect solution? Doesn’t exist. But we can shape the trade-offs so that all parties involved can live with them.

What does our experience with psi-exam show? Data protection-friendly e-examinations are possible – and without quality suffering. On the contrary: Through pseudonymous task-wise grading and the possibility of applying grading changes across examinations, equal treatment is better than with paper exams. Data minimization doesn’t have to be added on, it can be technically built in.

My position on AI is as follows: It’s not a panacea, but a tool with a clear profile. Excellent for task quality and grading dialogue, problematic for automation. The workload doesn’t decrease – it shifts. We don’t grade faster, but more thoroughly. That’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

I repeatedly hear that something is completely impossible – “Examinations on laptops without cabling – that’s not possible at all.” And then it is possible after all. This also applies to supposedly insurmountable data protection hurdles. You just have to take the time to talk to colleagues from the data protection office.

The exciting question is therefore not what is technically possible. Technology is usually much more flexible than thought. The question is: What do we want as a reasonable compromise between the desirable and the practicable? And there’s still much to explore.

In Short – The Complete Series

Privacy is shapeable: From technically enforced pseudonymity to zero-trust approaches – the possibilities are more diverse than thought.

AI is a tool, not a panacea: Quality assurance yes, automation (not yet) no.

Trade-offs remain: The perfect solution doesn’t exist, but we can consciously shape the balance.

The future is open: What is technically possible and what we want to implement pragmatically are two different questions – both deserve honest discussion.

This article concludes the series about my talk at the meeting of data protection officers from Bavarian universities. I’m happy to answer any questions and engage in discussion.

Bonus: From the Discussion

Remote Examinations: Less Relevant Than Thought

Experience: Despite technical possibilities, hardly any demand for remote examinations. Even Erasmus students prefer paper exams on-site abroad over proctored digital remote examinations. Is this perhaps a solution for a problem nobody has? At other universities, however, many aptitude assessment procedures run as remote examinations.