Control and Traceability: The Screenshot Solution (Part 3/4)

This is a translation. View original (Deutsch)

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

In this 3rd part we examine the challenge of evidence preservation: How do we ensure traceability without invasive surveillance?

Previously published:

Future part:

E-examinations must be legally secure. This means: preventing cheating attempts and being able to prove what actually happened in case of disputes. But how do we achieve this in a privacy-compliant way?

How Do We Ensure Traceability?

E-examinations must be accepted by examination offices and stand up in court. This means: We must prevent cheating attempts on one hand. On the other hand, we must be able to prove what actually happened in case of alleged disruptions or supposed defects in the procedure.

E-examination systems must defend against strong attacks: There are now USB Rubber Duckys the size of a USB plug: These are devices that pose as keyboards and can very quickly type several pages of text at the push of a button. Because of the privacy filters on the screens, it would hardly be possible for supervisors to see if someone copied the texts of all lecture slides into a text window during the exam.

Then there are students who claim during or after the exam that they had technical problems for ten minutes and now have a right to disability compensation. Even worse is the following claim after the exam: “I entered and saved something completely different from what was graded!” Statement against statement. Did the technology fail? Nobody knows – and nobody can convincingly explain what really happened.

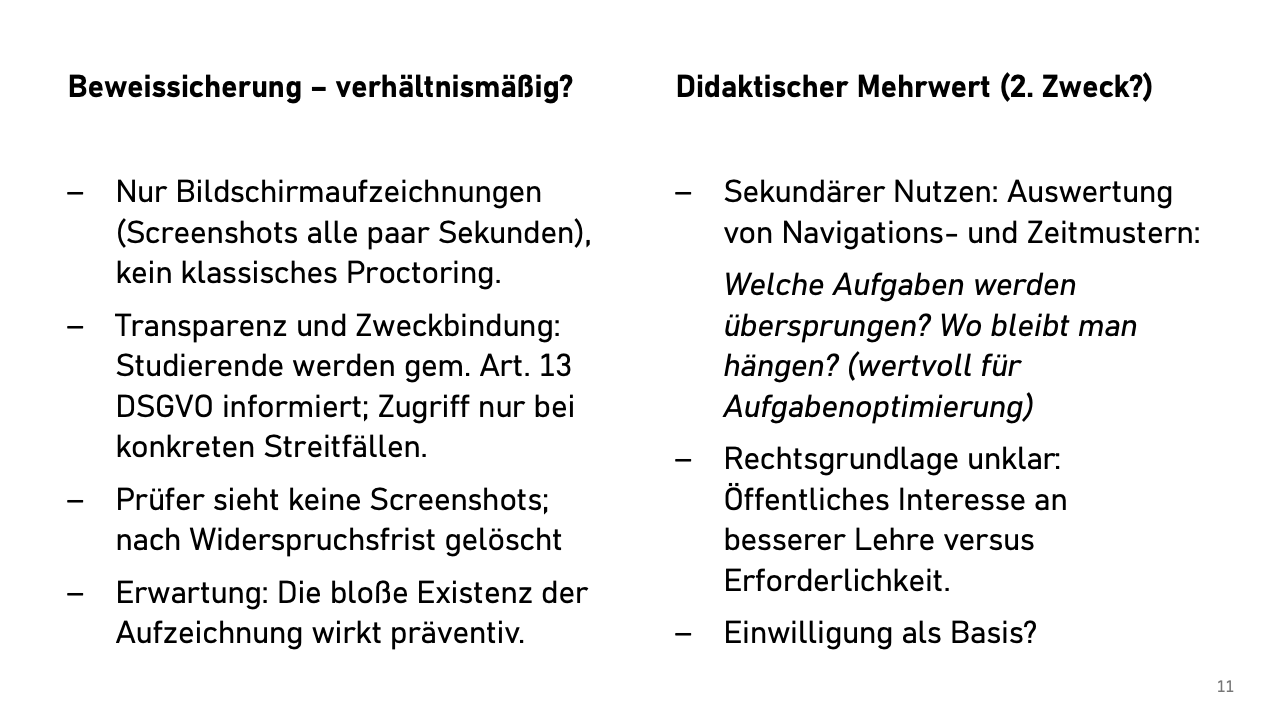

Our proposal for minimally invasive evidence preservation. We therefore intend to introduce screen recording. No cameras, no audio, no classic proctoring – that doesn’t make sense with 300 people in a room. Just screenshots every few seconds.

Our plan naturally considers the principles of data protection:

- Transparency: Students are informed in advance according to Art. 13 GDPR – thereby deterrent effect

- Separation: Screenshots are kept separately from examination answers

- Access control: Examiners do not receive the screenshots.

- Automatic deletion after expiration of the objection period.

- Purpose limitation: Evaluation only in concrete disputes and to prevent cheating attempts (whether without cause or only cause-related is still to be clarified)

The pure existence of the recording probably prevents more attempts than we will ever document.

Is this proportionate? We think so. The screenshots only document what happens on the examination screen – not the person, not the room. They are only looked at in case of suspicion or conflict. And they are automatically deleted.

The screenshots could also be didactically valuable after grading. How do students navigate through the examination? Where do they spend most time? Which tasks are skipped? How do they revise errors?

Some colleagues would like to use such data to improve their examinations. But the legal basis? Public interest in good teaching? Consent? We are still cautious here until this is clarified in terms of data protection law.

Data protection and traceability famously form an area of tension. We can try to resolve the goal conflict between anonymity and control through technology and organizational measures as well as possible for the parties involved.

Speaking of anonymity – to conclude, I want to show how far one could drive data protection if one really wanted to…

In Short – Part 3

Minimally invasive evidence preservation: Screenshots every few seconds – no cameras, no audio, no classic proctoring.

Deterrence works: The pure existence of the recording prevents more attempts than are documented.

Privacy by design: Automatic deletion, purpose limitation, and strict access control protect privacy.

In the final part of our series, we take it to the extreme: What could genuine anonymity in examinations look like – with a surprisingly analog solution.

Bonus: From the Discussion

Screen Recording and Data Protection

Discussion: Screen recording was intensively discussed. From a data protection perspective, it appeared implementable under the given conditions:

- Clear purpose limitation (only in disputes)

- Transparency (Art. 13 GDPR information)

- Automatic deletion after objection period

- No access for examiners, only for examination committee when needed

Alternative approaches like recording keystrokes were discussed, but this doesn’t prove everything and possibly involves biometric data (Art. 9 GDPR).

Cheating Attempts and Practical Use Cases

Illustrative examples from the discussion: A fictional example for the necessity of screenshots: A student puzzles over a task for ten minutes, scrolls the text back and forth. Then the person goes to the bathroom, comes back after seven minutes, and writes the perfect answer. What happened? A flash of inspiration in the bathroom or something else? The screenshots would document such anomalies.

Similarly, one could detect if someone gains internet access through security holes on the laptops and accesses ChatGPT during the exam. Or if someone pastes text from the clipboard (not suspicious in itself), but then the following text appears on screen: “As a large language model, I believe you should answer this task as follows” – and deletes this text from the form fields before submitting the exam.

Limitation: No live monitoring or AI evaluation of screenshots planned. This would undermine the high reliability requirements – if AI analysis fails due to power outage or network disruptions, this must not endanger the entire exam. Instead, only retrospective manual evaluation in concrete suspicion cases.

Time Management and Flexible Processing Times

Discussion about time extensions: Why doesn’t the system automatically lock editing capability when exam time has expired? My answer: Because we want to give supervisors uncomplicated full control over exam conduct. As with paper exams, supervisors should be able to react flexibly.

Practical example: We already had an emergency medical response in the examination room during the exam; immediately adjacent students received spontaneous time extensions from supervisors – without having to look up computer numbers and configure the extension in a system.

Here too, screenshots show their utility: If someone continues writing after official end, this is documented. As with paper exams, an exam can thereby be declared invalid after the end of processing time for such rule violations. Certainly debatable, but I think: It should also be possible to fail an exam for such rule violations in e-examinations.