AI in Practice: Opportunities and Limits in E-Examinations (Part 2/4)

This is a translation. View original (Deutsch)

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

In this 2nd part we examine the practical use of AI in e-examinations: What works, what doesn’t, and why automatic evaluation is still a thing of the future.

Previously published:

Future parts:

In the first part, we got to know the foundations of psi-exam and the fundamental goal conflicts in e-examinations. Now we turn to the question of how AI tools can be concretely used – and where the limits lie.

AI in Examination Use: Pragmatic Practice

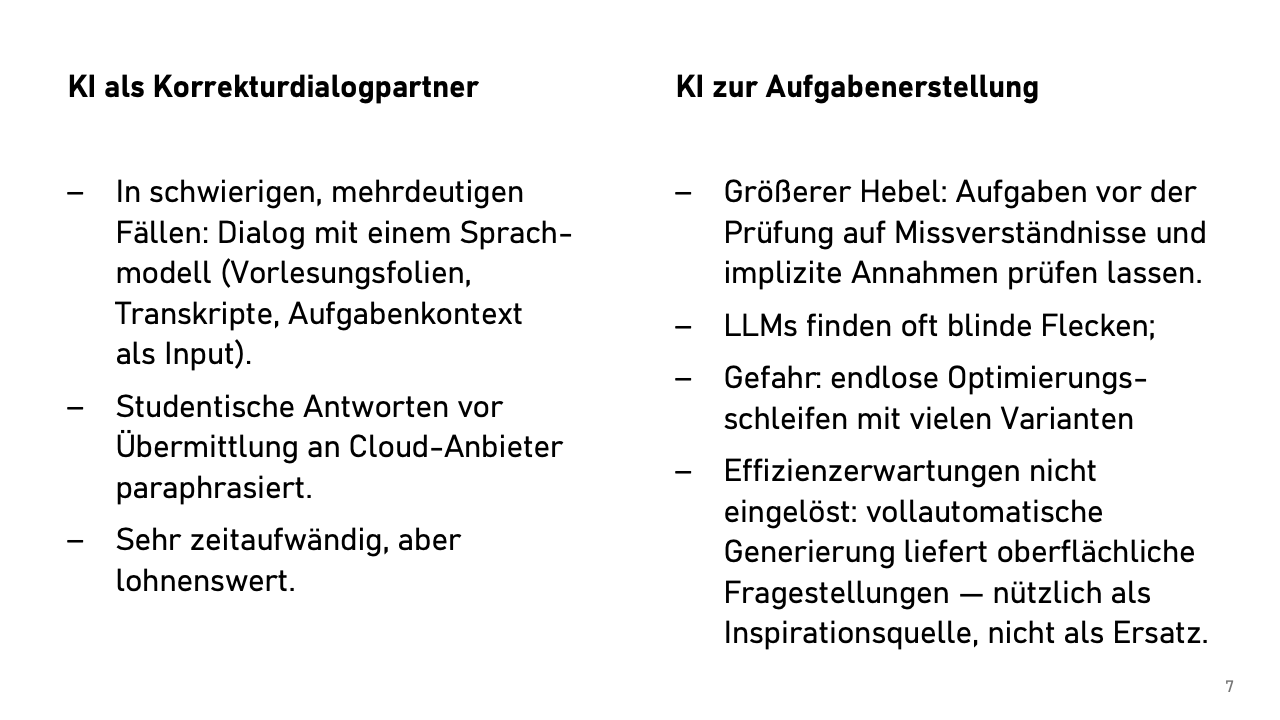

The first AI application arose from practice. During grading, you repeatedly encounter answers that make you ponder: Not wrong, not right, but… different. Previously, you might have asked a colleague – if you could find someone who had time and inclination to think into the problem. Today we can simply do this with a language model. AI becomes a grading dialogue partner.

In fact, the incentive for examiners to look more closely at borderline cases is greater with our system than usual. After all, the low-threshold online review otherwise threatens a real danger that test-takers will complain about borderline grading – and reacting to that then definitely costs more work. So examiners have an incentive to be thorough during grading.

The process looks like this: We paraphrase the test-takers’ answers (copyright, data protection!), give the language model lecture slides, possibly also lecture transcripts, the concrete task formulation and neighboring tasks, and then ask essentially: “Could this person’s interpretation also be a valid answer to the question when we actually expected the following answer, or is the answer technically wrong or too ambiguous?”

The result: Extremely well-founded, half-page justifications for why an answer is right or wrong, or why it is actually wrong but “given the ambiguous formulation on lecture slide 47 bottom left” could well be considered correct.

Time-consuming? Absolutely. You only do this for a few answers per exam. But these cases often reveal ambiguities or errors in lecture materials that we weren’t previously aware of.

The bigger leverage in AI use by examiners lies in examination creation. We develop new tasks for almost every exam because we provide students with all past exams with sample solutions for transparency reasons. We have high requirements for new tasks: they must be fair, precise, and unambiguous.

Current AI tools excel here. We ask: “Is this formulation also understandable for our students from Asia? Can we assume they understand the terms used in the task (‘mountain station’ and ‘alpine hut’)?” What is normal for us can be highly confusing for people from other cultural backgrounds. The models regularly find blind spots, provide assessments of fairness and difficulty level.

The downside: You can lose yourself in endless optimization loops. After three hours, you have 37 variants of a task, none clearly better. Certainly no time savings, but perhaps better examination questions. Those prone to procrastination should perhaps set a timer.

Naturally, we have also tried to have complete examinations generated. “Create five tasks for each topic area from the lecture (based on the uploaded material).” The result? Multiple-choice and definition queries. Technically correct, didactically irrelevant – not very useful for us.

Nevertheless, AI tools are a great help in task creation, whether with new example scenarios, clever variations of standard tasks, or alternative formulations. So: Good for inspiration, not yet a replacement for human task creation.

AI for Automatic Evaluation

The temptation is great: Upload all answers, get back a grade list. The reality is sobering.

With cloud models (GPT-4, Claude), evaluation works surprisingly well – but data protection-wise it’s a nightmare. EU AI Act, GDPR, high-risk area under AI regulation, passing examination data to US providers… even with a data processing agreement, we’re moving on thin ice.

What about local models? At least the data protection problem could be solved somewhat more easily. The quality? Current 7-billion-parameter models are unusable for grading our programming and free-text tasks; they make far too many (subtle) errors. With large models with 70 billion parameters, it looks better, but still unsatisfying.

But the actual problem is different, it’s psychological in nature: AI’s evaluation suggestions always sound plausible. After 20 assessments, you might become careless and not look so closely anymore; it’ll be fine! The “final check” by examiners is exhausting work! You have to read the answer, then the AI assessment, and then check if they match. Automated evaluation creates more effort than forming your own opinion. I see no gain in this, only more work and especially unnecessary attack surface.

I’ve talked to people at other examination symposiums who are more euphoric. I don’t yet know exactly what we need to do so they don’t go down the wrong path.

Learning Analytics – we don’t do this yet. Theoretically, we could also link data from the learning management system with examination results: “Attention! Students with similar learning behavior to yours had 30 points less in the exam.” A colleague researches this with impressive results: Such feedback interventions lead to higher participation rates in examinations and also to better examination performance.

Ethically problematic? A mammoth project in terms of data protection? Probably, yes! Therefore not currently implemented with us, but a good topic for discussion.

AI tools are not miracle weapons for examiners, but tools: Good for quality assurance and reflection; automation is problematic. The workload doesn’t decrease, it shifts. Instead of grading faster, we grade more thoroughly. But that’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

But wait – haven’t we forgotten something? What about the second part of our second goal conflict: How do we prevent cheating attempts or uncover them? Couldn’t you use an AI for that… no, absolutely not!

In Short – Part 2

AI as a tool, not a replacement: Strengths in quality assurance and task testing, weaknesses in automatic evaluation.

The workload shifts: We don’t grade faster, but more thoroughly – a feature, not a bug.

Privacy remains critical: Cloud models work well but are legally problematic. Local models are not yet mature.

In the next part, we’ll dedicate ourselves to the delicate balance between data protection and control: How do we prevent cheating attempts without violating privacy?

From the Discussion

AI as First Examiner?

Question: Could the first grading be done completely by AI and only the second examiners look over it?

Answer: Technically feasible, but probably legally and psychologically problematic. With current technology, second examiners would factually have to completely re-grade everything – that’s more work for them, not less. The psychological trap: AI evaluations always sound plausible, the temptation to adopt them unchecked is real.

Other Technical Solutions

Input from the audience:

- Case Train (University of Würzburg): individual time extension possible, analysis of typing behavior for cheating detection (copy-paste behavior)

- Proctorio and other US providers: Third-country transfer problems, fundamental rights interventions when using private devices