psi-exam and Goal Conflicts in E-Examinations (Part 1/4)

This is a translation. View original (Deutsch)

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

This is Part 1 of 4 of a comprehensive article series based on my talk at the meeting of data protection officers from Bavarian universities on September 17, 2025, at the University of Bamberg.

In this series:

- The Foundations – psi-exam and the Goal Conflicts (this article)

- AI in Practice – Opportunities and Limits

- Control and Traceability – The Screenshot Solution

- Zero-Trust Vision – TEARS and Outlook

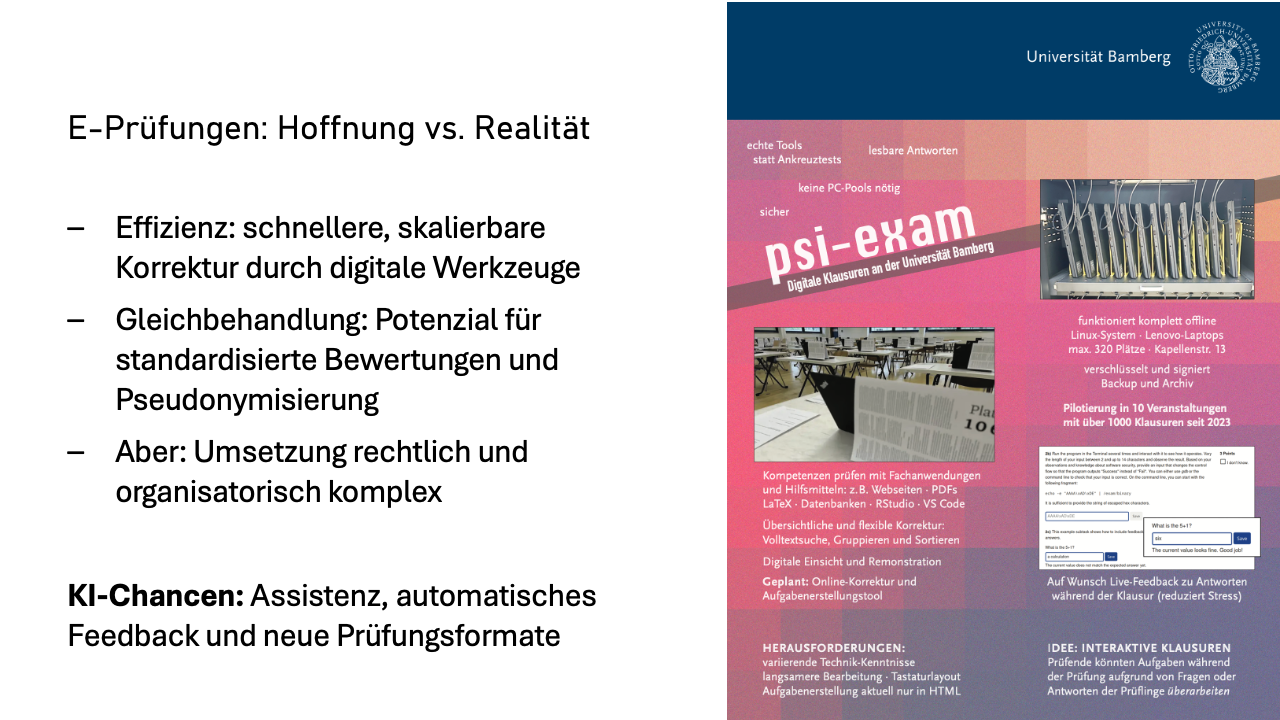

Electronic exams promise a lot: more efficient grading, better equal treatment, new possibilities through AI. In practice, however, these promises collide with strict requirements for data protection and examination law.

At the University of Bamberg, we have been developing an e-examination system since 2022. We can examine up to 340 test-takers simultaneously on laptops in a single room. Currently, the system is used in about ten courses with more than 600 test-takers annually.

During development and in productive operation, we constantly have to weigh competing objectives. I have encountered two goal conflicts that we will examine more closely in this article series.

The first conflict is: Privacy versus AI benefits. Recently, new innovations are coming to the examination landscape. From all sides, there is a desire to use the next technological innovation for better testing: large language models, usually simply referred to as “AI” – ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or similar.

Some examiners expect great benefits from AI tools for examinations and criticize the data protection hurdles that prevent them from benefiting. Students, on the other hand, don’t want their data to be passed on anywhere they have no control over – for good reason, I think. This restricts us as examiners. The impressive capabilities of large language models that we use privately every day cannot be used at the university.

The greatest temptation is naturally automatic grading – and this isn’t about multiple-choice questions, where automated evaluation has been common for a long time, but about free-text answers. But improving the quality of question formulations could also be an interesting application for AI tools.

The crucial question: Is there somewhere in the continuum between “give away all data” (maximum AI benefit) and “don’t do anything with it” use cases that provide benefits?

Now to the second conflict: Anonymity versus control. Students repeatedly tell me about reservations regarding the neutrality of examiners – especially in other faculties. In student committees, accusations are sometimes even made that grading is not fair, whether due to origin, gender, or other personal characteristics.

The desire for anonymous grading of examinations is therefore understandable. That intended and unintended biases can occur in non-anonymous evaluation has, to my knowledge, also been proven in studies. Examination offices, however, quickly dismiss this topic: “That’s impossible – our processes are based on names and student ID numbers.”

At the same time, we also need the opposite of anonymity – traceability and control, namely to prevent cheating attempts.

The second goal conflict therefore has several facets:

- Fair evaluation requires pseudonymous or, better yet, completely anonymous grading.

- For legal certainty, we need fraud control and evidence preservation.

- And then there’s another problem: the power imbalance between university and students. The university sets the rules and provides the technology. Students are largely at its mercy, have little influence, and limited insight. Hard to accept.

Before I show how we address these conflicts, I have to acknowledge one limitation: The focus of this series is exclusively on written e-examinations under supervision.

We have factually given up on homework assignments given the large quality differences between free and commercial AI tools – equal opportunity can no longer be guaranteed. And AI detectors? An opaque black box with error rates that we don’t want to base examination decisions on.

psi-exam: Privacy-Friendly E-Examinations

We now take a brief look at our psi-exam system and how it already offers significant advantages over conventional written exams without AI.

Visit the psi-exam website that provides more details about the system as well as a video introduction we show to our students.

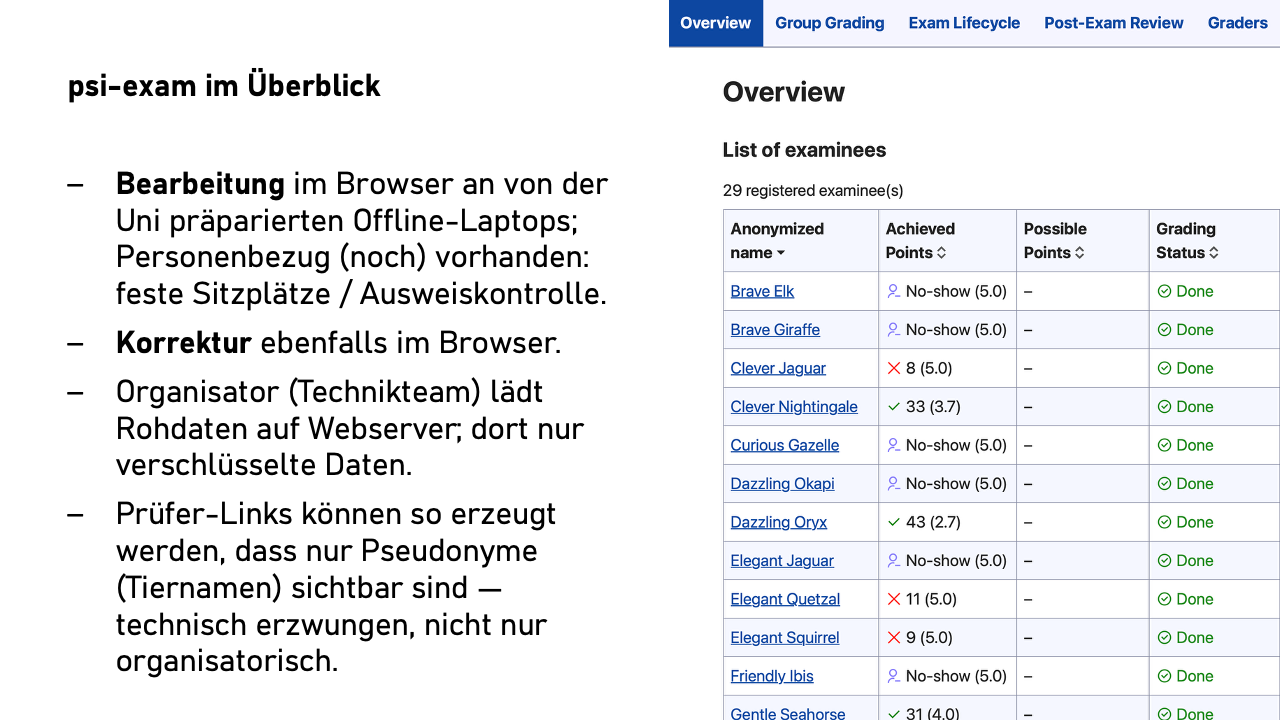

psi-exam is a browser-based examination system for up to 350 students simultaneously. We have about 380 Linux laptops that we can quickly set up and tear down in the university’s examination room – there is neither space nor money for dedicated e-examination rooms at our university.

Students work on tasks in form fields in the browser. Identity verification takes place during the exam at the seat, so we know: Maria Müller sat in seat 37, and her ID confirms her identity.

After the end of the exam, all answers are uploaded encrypted. But – and this is where it gets interesting – the server only sees ciphertext. The keys lie exclusively with the e-examination organizer.

This person generates an invitation link with a special key for the examiners. The key point: When generating, the organizer decides whether this key displays real names or only pseudonyms. Instead of student names, animal names are then displayed, such as “Brave Elk,” “Clever Jaguar,” and “Curious Panda.”

The crucial point: The examiners do not have the ability to see the real names – pseudonymity is not a question of discipline or trust, but technically enforced.

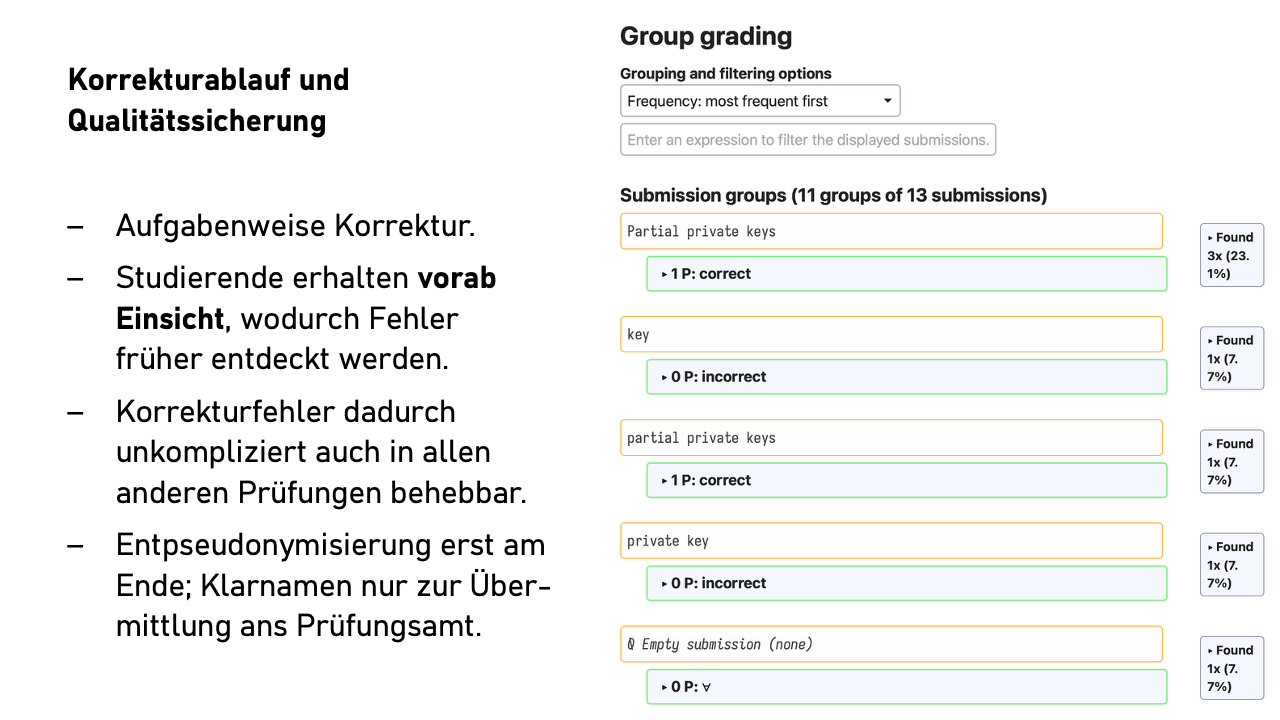

Grading is done task by task. So first all answers to task 1a, then 1b, and so on. The order is configurable: by answer length, alphabetically by the first word of the answer, but naturally not by person name. We’re talking about free-text answers here, not multiple-choice questions.

If we now first discover a systematic grading error during the review, we fix the error immediately in all other affected examinations – unthinkable with paper exams.

This has two effects: First, it saves mental energy through the consistent context between successive answers. Second, similar or identical answers end up directly after each other. When twenty students answer identically or almost identically, this can be evaluated quickly and consistently.

You can also filter by keywords or, for yes/no questions with justification, grade all “yes” answers together. This significantly increases the comfort factor without data protection implications.

Examiners can generate additional invitation links – for tutors for pre-grading or for second examiners. These links can also be configured pseudonymously. The second examiners only see those who failed, can view the first evaluation and comment on it.

The system implements data minimization: We don’t store personal data about examiners or second examiners. Examiners have city names in the system. The organizer only knows the identity of the first examiners, but not whom the first examiners invited for grading or second grading.

Review before grade announcement. Here we deviate radically from the usual process. Directly after the first grading – still before the second grading and long before transmitting grades to the examination office – students receive individual review links. They see their answers, the evaluation, and a sample solution.

This completely changes the dynamics: The effort for reviewing is much lower than with paper exams. It’s also a more pleasant situation for students. They communicate directly with the first examiners, not with the – possibly intimidating – examination office. They have a strong personal incentive to look closely and can often better judge than subject-foreign second examiners whether their alternative interpretation of a task might not be a valid answer after all.

If a student provides convincing argumentation – perhaps due to an ambiguous task formulation – we can react. And here the actual advantage of digital examinations comes into play: With one click, we can then search all 350 examinations for similar answers and adjust points everywhere.

On paper, no one would request the entire stack from the examination office just because one exam received two more points after review. Digitally, this costs us almost nothing – and we must treat everyone equally.

At the end of the process, pseudonymization is lifted. Either the organizer takes this over (they have the original data from the laptops), or they send the examiners a new link after completion of grading that displays the real names.

What have we achieved so far? I have presented our psi-exam system, which technically enforces pseudonymous grading while remaining flexible enough for the reality of examination operations. Data minimization is built in, not added on. Equal treatment is better than with paper exams through task-wise grading and the possibility of subsequent adjustment.

But we have so far only addressed one side of our goal conflicts. What about AI? How can examiners benefit from AI tools? And how does data minimization look there?

In Short – Part 1

psi-exam shows: Privacy-friendly e-examinations are possible – with technically enforced pseudonymity, task-wise grading, and improved equal treatment compared to paper exams.

The goal conflicts remain: Privacy vs. AI benefits as well as anonymity vs. control shape further development.

The journey is the destination: Data minimization doesn’t have to be added on, it can be technically built in.

In the next part of the series, we’ll look at how AI tools can be concretely used in e-examinations – and where the limits lie. Spoiler: Automatic grading is not as useful as you might expect.

Bonus: Notes from the Discussion

Task Types and Limitations

Question: Which task types don’t work well electronically?

Answer: Drawings, sketches, mathematical derivations with many symbols are difficult. Pragmatic solution: These parts continue on paper, then scan and merge with electronic parts. Alternative: Prepared diagrams for annotation.

Documentation and Compliance

Questions about data protection documentation: The current system has:

- Basic process documentation

- Art. 13 GDPR information for all parties involved

- Checklists for exam conduct

- Archiving concept with deletion periods

Still missing: Formal processing documentation (will be created when needed). Opinion in the room: Technical documentation together with data protection basic considerations meets data protection documentation requirements at least basically.

Institutional Challenges

Reality: The system currently runs as a “functional prototype” at my chair, still financed by third-party funds for the next few years, not as a university service. Transfer to regular operation will require:

- Enhancement of technical implementation for regular operation

- Dedicated personnel, training of existing administrative staff

- More comprehensive documentation

- Political will and financing

Pragmatism: “Best effort” – it works, thousands of examinations have been conducted, within the framework of the BaKuLe project the transfer to regular operation is being explored and carried out.