Anonymous Exams, Better Grading: AI and Privacy in Practice

This is a translation.

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

This is Part 1 of 4 of a comprehensive article series based on my talk at the meeting of data protection officers from Bavarian universities on September 17, 2025, at the University of Bamberg.

In this series:

- The Foundations – psi-exam and the Goal Conflicts (this article)

- AI in Practice – Opportunities and Limits

- Control and Traceability – The Screenshot Solution

- Zero-Trust Vision – TEARS and Outlook

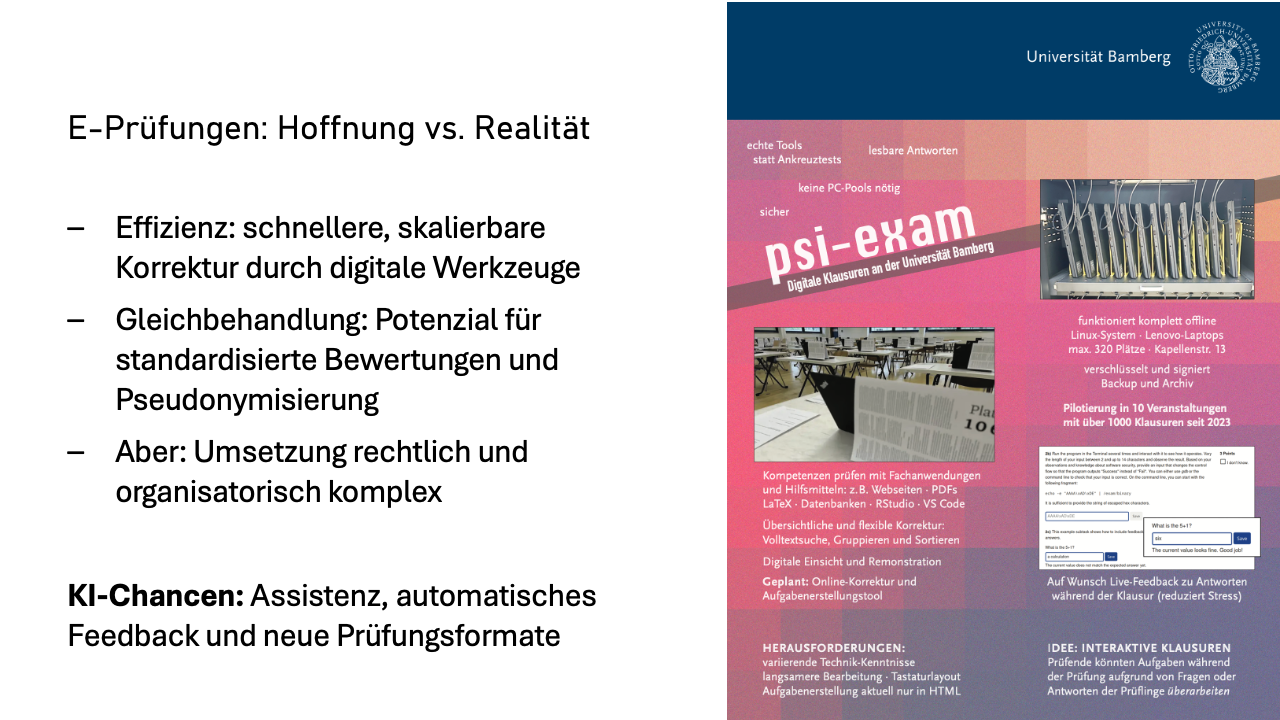

Electronic exams promise a lot: more efficient grading, better equal treatment, new possibilities through AI. In practice, however, these promises collide with strict requirements for data protection and examination law.

At the University of Bamberg, we have been developing an e-examination system since 2022. We can examine up to 340 test-takers simultaneously on laptops in a single room. Currently, the system is used in about ten modules with more than 600 test-takers annually.

During development and in productive operation, we constantly have to weigh competing objectives. I have encountered two goal conflicts that we will examine more closely below.

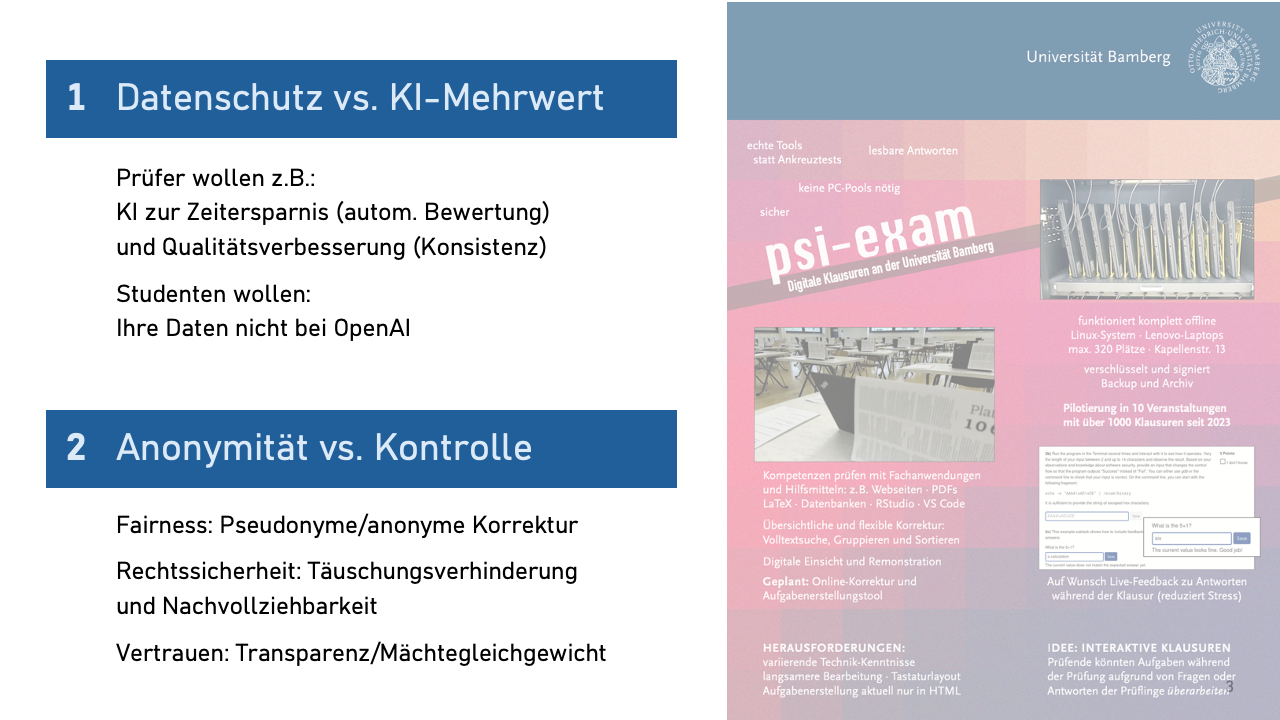

The first conflict is: Privacy versus AI benefits. Recently, new innovations are coming to the examination landscape. From all sides, there is a desire to use the next technological innovation for better testing: large language models, usually simply referred to as “AI” – ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or similar.

Some examiners expect great benefits from AI tools for examinations and criticize the data protection hurdles that prevent them from benefiting. Students, on the other hand, don’t want their data to be passed on anywhere they have no control over – for good reason, I think. This restricts us as examiners. The impressive capabilities of large language models that we use privately every day cannot be used at the university.

The greatest temptation is naturally automatic grading – and this isn’t about multiple-choice questions, where automated evaluation has been common for a long time, but about free-text answers. But improving the quality of question formulations could also be an interesting application for AI tools.

The crucial question: Is there somewhere in the continuum between “give away all data” (maximum AI benefit) and “don’t do anything with it” use cases that provide benefits?

Now to the second conflict: Anonymity versus control. Students repeatedly tell me about reservations regarding the neutrality of examiners – especially in other faculties. In student committees, accusations are sometimes even made that grading is not fair, whether due to origin, gender, or other personal characteristics.

The desire for anonymous grading of examinations is therefore understandable. That intended and unintended biases can occur in non-anonymous evaluation has, to my knowledge, also been proven in studies. Examination offices, however, quickly dismiss this topic: “That’s impossible – our processes are based on names and student ID numbers.”

At the same time, we also need the opposite of anonymity – traceability and control, namely to prevent cheating attempts.

The second goal conflict therefore has several facets:

- Fair evaluation requires pseudonymous or, better yet, completely anonymous grading.

- For legal certainty, we need fraud control and evidence preservation.

- And then there’s another problem: the power imbalance between university and students. The university sets the rules and provides the technology. Students are largely at its mercy, have little influence, and limited insight. Hard to accept.

Before I show how we address these conflicts, the following limitation: The focus below is exclusively on written e-examinations under supervision.

We have factually given up on homework assignments given the large quality differences between free and commercial AI tools – equal opportunity can no longer be guaranteed. And AI detectors? An opaque black box with error rates that we don’t want to base examination decisions on.

psi-exam: Privacy-Friendly E-Examinations

We now take a brief look at our psi-exam system and how it already offers significant advantages over conventional written exams without AI.

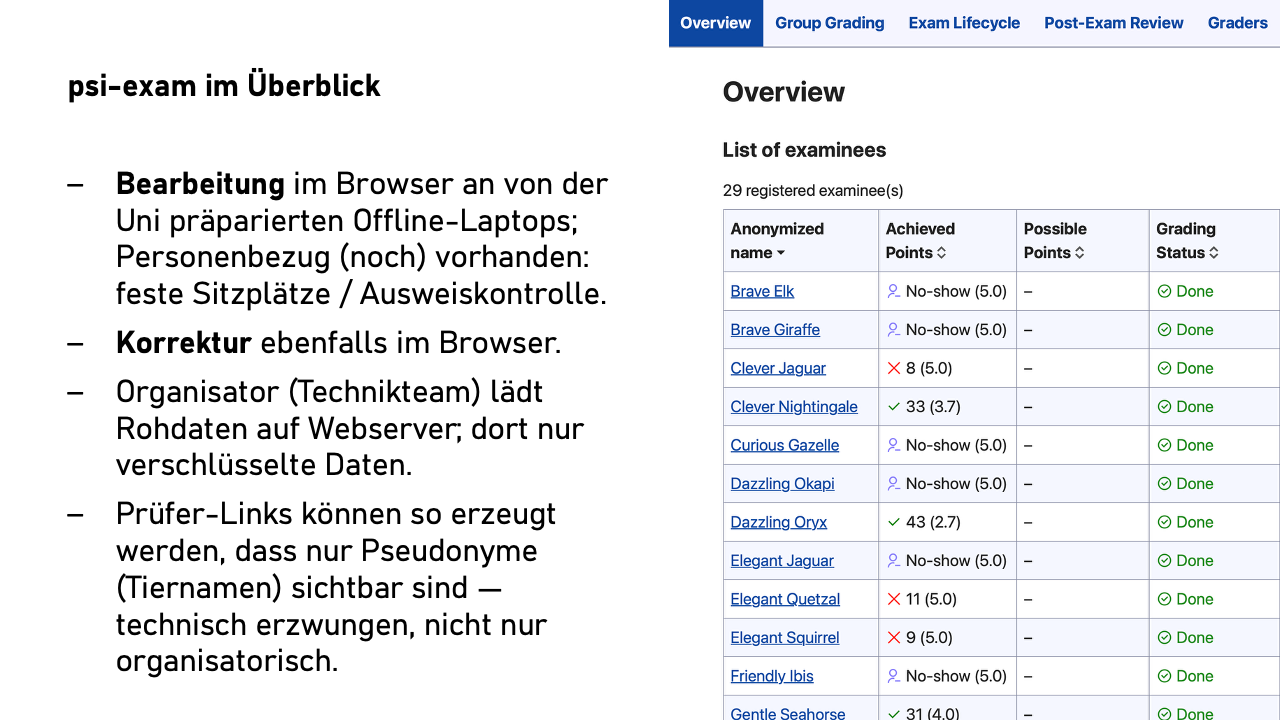

psi-exam (website with details) is a browser-based examination system for up to 350 students simultaneously. We have about 380 Linux laptops that we can quickly set up and tear down in the university’s examination room – there is neither space nor money for dedicated e-examination rooms at our university.

Students work on tasks in form fields in the browser. Identity verification takes place during the exam at the seat, so we know: Maria Müller sat in seat 37, and her ID confirms her identity.

After the end of the exam, all answers are uploaded encrypted. But – and this is where it gets interesting – the server only sees ciphertext. The keys lie exclusively with the e-examination organizer.

This person generates an invitation link with a special key for the examiners. The key point: When generating, the organizer decides whether this key displays real names or only pseudonyms. Instead of student names, animal names are then displayed, such as “Brave Elk,” “Clever Jaguar,” and “Curious Panda.”

The crucial point: The examiners do not have the ability to see the real names – pseudonymity is not a question of discipline or trust, but technically enforced.

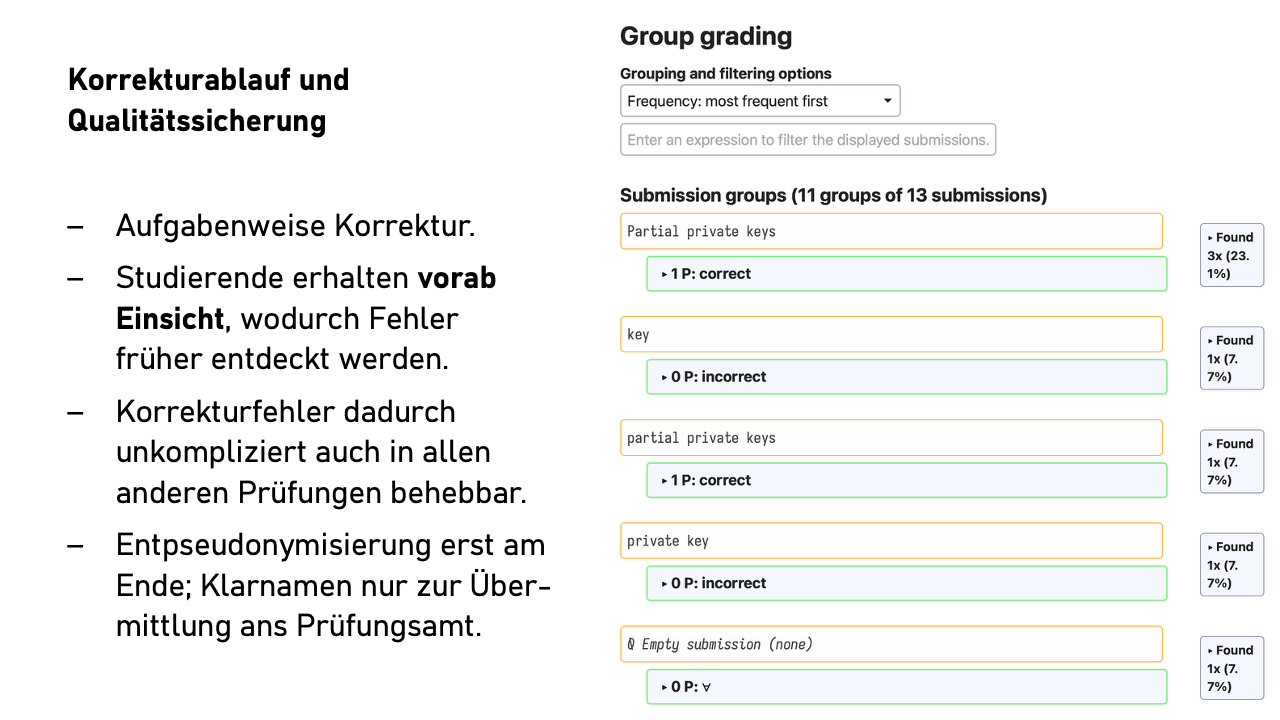

Grading is done task by task. So first all answers to task 1a, then 1b, and so on. The order is configurable: by answer length, alphabetically by the first word of the answer, but naturally not by person name. We’re talking about free-text answers here, not multiple-choice questions.

If we now first discover a systematic grading error during the review, we fix the error immediately in all other affected examinations – unthinkable with paper exams.

This has two effects: First, it saves mental energy through the consistent context between successive answers. Second, similar or identical answers end up directly after each other. When twenty students answer identically or almost identically, this can be evaluated quickly and consistently.

You can also filter by keywords or, for yes/no questions with justification, grade all “yes” answers together. This significantly increases the comfort factor without data protection implications.

Examiners can generate additional invitation links – for tutors for pre-grading or for second examiners. These links can also be configured pseudonymously. The second examiners only see those who failed, can view the first evaluation and comment on it.

The system implements data minimization: We don’t store personal data about examiners or second examiners. Examiners have city names in the system. The organizer only knows the identity of the first examiners, but not whom the first examiners invited for grading or second grading.

Review before grade announcement. Here we deviate radically from the usual process. Directly after the first grading – still before the second grading and long before transmitting grades to the examination office – students receive individual review links. They see their answers, the evaluation, and a sample solution.

This completely changes the dynamics: The effort for reviewing is much lower than with paper exams. It’s also a more pleasant situation for students. They communicate directly with the first examiners, not with the – possibly intimidating – examination office. They have a strong personal incentive to look closely and can often better judge than subject-foreign second examiners whether their alternative interpretation of a task might not be a valid answer after all.

If a student provides convincing argumentation – perhaps due to an ambiguous task formulation – we can react. And here the actual advantage of digital examinations comes into play: With one click, we can then search all 350 examinations for similar answers and adjust points everywhere.

On paper, no one would request the entire stack from the examination office just because one exam received two more points after review. Digitally, this costs us almost nothing – and we must treat everyone equally.

At the end of the process, pseudonymization is lifted. Either the organizer takes this over (they have the original data from the laptops), or they send the examiners a new link after completion of grading that displays the real names.

What have we achieved so far? I have presented our psi-exam system, which technically enforces pseudonymous grading while remaining flexible enough for the reality of examination operations. Data minimization is built in, not added on. Equal treatment is better than with paper exams through task-wise grading and the possibility of subsequent adjustment.

But we have so far only addressed one side of our goal conflicts. What about AI? How can examiners benefit from AI tools? And how does data minimization look there?

In Short – Part 1

psi-exam shows: Privacy-friendly e-examinations are possible – with technically enforced pseudonymity, task-wise grading, and improved equal treatment compared to paper exams.

The goal conflicts remain: Privacy vs. AI benefits as well as anonymity vs. control shape further development.

The journey is the destination: Data minimization doesn’t have to be added on, it can be technically built in.

In the next part of the series, we’ll look at how AI tools can be concretely used in e-examinations – and where the limits lie. Spoiler: Automatic grading is not what you expect.

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

This is Part 2 of 4 of our series on e-examinations, AI, and privacy.

Previously published:

In this part: We examine the practical use of AI in e-examinations: What works, what doesn’t, and why automatic evaluation is still a thing of the future.

In the first part, we got to know the foundations of psi-exam and the fundamental goal conflicts in e-examinations. Now we turn to the question of how AI tools can be concretely used – and where the limits lie.

AI in Examination Use: Pragmatic Practice

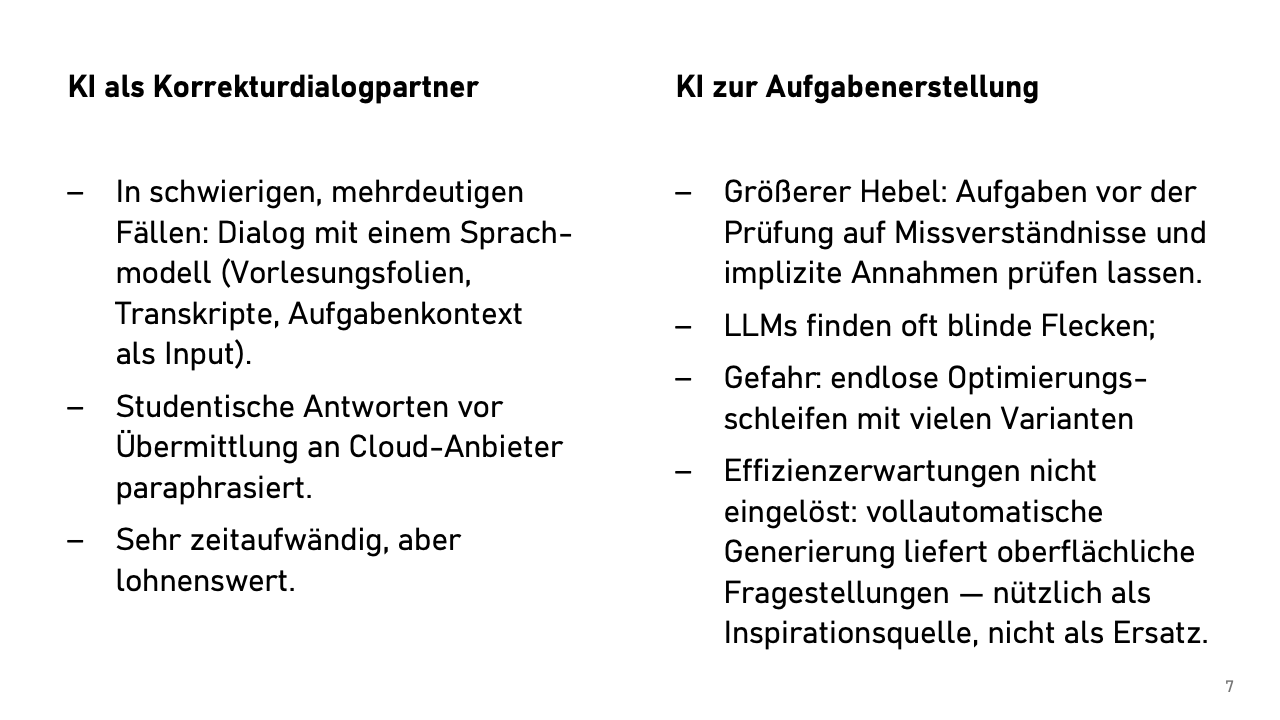

The first AI application arose from practice. During grading, you repeatedly encounter answers that make you ponder: Not wrong, not right, but… different. Previously, you might have asked a colleague – if you could find someone who had time and inclination to think into the problem. Today we can simply do this with a language model. AI becomes a grading dialogue partner.

In fact, the incentive for examiners to look more closely at borderline cases is greater with our system than usual. After all, the low-threshold online review otherwise threatens a real danger that test-takers will complain about borderline grading – and reacting to that then definitely costs more work. So examiners have an incentive to be thorough during grading.

The process looks like this: We paraphrase the test-takers’ answers (copyright, data protection!), give the language model lecture slides, possibly also lecture transcripts, the concrete task formulation and neighboring tasks, and then ask essentially: “Could this person’s interpretation also be a valid answer to the question when we actually expected the following answer, or is the answer technically wrong or too ambiguous?”

The result: Extremely well-founded, half-page justifications for why an answer is right or wrong, or why it is actually wrong but “given the ambiguous formulation on lecture slide 47 bottom left” could well be considered correct.

Time-consuming? Absolutely. You only do this for a few answers per exam. But these cases often reveal ambiguities or errors in lecture materials that we weren’t previously aware of.

The bigger leverage in AI use by examiners lies in examination creation. We develop new tasks for almost every exam because we provide students with all past exams with sample solutions for transparency reasons. We have high requirements for new tasks: they must be fair, precise, and unambiguous.

Current AI tools excel here. We ask: “Is this formulation also understandable for our students from Asia? Can we assume they understand the terms used in the task (‘mountain station’ and ‘alpine hut’)?” What is normal for us can be highly confusing for people from other cultural backgrounds. The models regularly find blind spots, provide assessments of fairness and difficulty level.

The downside: You can lose yourself in endless optimization loops. After three hours, you have 37 variants of a task, none clearly better. Certainly no time savings, but perhaps better examination questions. Those prone to procrastination should perhaps set a timer.

Naturally, we have also tried to have complete examinations generated. “Create five tasks for each topic area from the lecture (based on the uploaded material).” The result? Multiple-choice and definition queries. Technically correct, didactically irrelevant – not very useful for us.

Nevertheless, AI tools are a great help in task creation, whether with new example scenarios, clever variations of standard tasks, or alternative formulations. So: Good for inspiration, not yet a replacement for human task creation.

AI for Automatic Evaluation

The temptation is great: Upload all answers, get back a grade list. The reality is sobering.

With cloud models (GPT-4, Claude), evaluation works surprisingly well – but data protection-wise it’s a nightmare. EU AI Act, GDPR, high-risk area under AI regulation, passing examination data to US providers… even with a data processing agreement, we’re moving on thin ice.

What about local models? At least the data protection problem could be solved somewhat more easily. The quality? Current 7-billion-parameter models are unusable for grading our programming and free-text tasks; they make far too many (subtle) errors. With large models with 70 billion parameters, it looks better, but still unsatisfying.

But the actual problem is different, it’s psychological in nature: AI’s evaluation suggestions always sound plausible. After 20 assessments, you might become careless and not look so closely anymore; it’ll be fine! The “final check” by examiners is exhausting work! You have to read the answer, then the AI assessment, and then check if they match. Automated evaluation creates more effort than forming your own opinion. I see no gain in this, only more work and especially unnecessary attack surface.

I’ve talked to people at other examination symposiums who are more euphoric. I don’t yet know exactly what we need to do so they don’t go down the wrong path.

Learning Analytics – we don’t do this yet. Theoretically, we could also link data from the learning management system with examination results: “Attention! Students with similar learning behavior to yours had 30 points less in the exam.” A colleague researches this with impressive results: Such feedback interventions lead to higher participation rates in examinations and also to better examination performance.

Ethically problematic? A mammoth project in terms of data protection? Probably, yes! Therefore not currently implemented with us, but a good topic for discussion.

AI tools are not miracle weapons for examiners, but tools: Good for quality assurance and reflection; automation is problematic. The workload doesn’t decrease, it shifts. Instead of grading faster, we grade more thoroughly. But that’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

But wait – haven’t we forgotten something? What about the second part of our second goal conflict: How do we prevent cheating attempts or uncover them? Couldn’t you use an AI for that… no, absolutely not!

In Short – Part 2

AI as a tool, not a replacement: Strengths in quality assurance and task testing, weaknesses in automatic evaluation.

The workload shifts: We don’t grade faster, but more thoroughly – a feature, not a bug.

Privacy remains critical: Cloud models work well but are legally problematic. Local models are not yet mature.

In the next part, we’ll dedicate ourselves to the delicate balance between anonymity and control: How do we prevent cheating attempts without violating privacy?

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

This is Part 3 of 4 of our series on e-examinations, AI, and privacy.

Previously published:

In this part: The challenge of evidence preservation: How do we ensure traceability without invasive surveillance?

E-examinations must be legally secure. This means: preventing cheating attempts and being able to prove what actually happened in case of disputes. But how do we achieve this in a privacy-compliant way?

How Do We Ensure Traceability?

E-examinations must be accepted by examination offices and stand up in court. This means: We must prevent cheating attempts on one hand. On the other hand, we must be able to prove what actually happened in case of alleged disruptions or supposed defects in the procedure.

E-examination systems must defend against strong attacks: There are now USB Rubber Duckys the size of a USB plug: These are devices that pose as keyboards and can very quickly type several pages of text at the push of a button. Because of the privacy filters on the screens, it would hardly be possible for supervisors to see if someone copied the texts of all lecture slides into a text window during the exam.

Then there are students who claim during or after the exam that they had technical problems for ten minutes and now have a right to disability compensation. Even worse is the following claim after the exam: “I entered and saved something completely different from what was graded!” Statement against statement. Did the technology fail? Nobody knows – and nobody can convincingly explain what really happened.

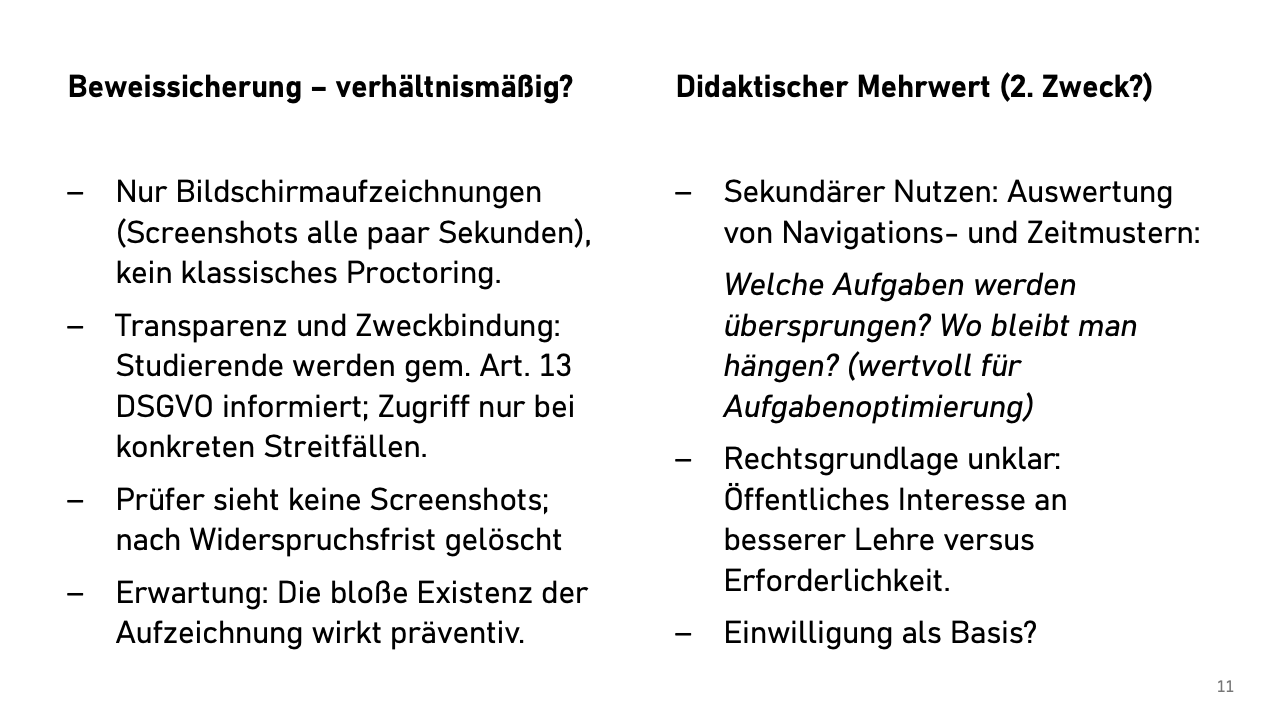

Our proposal for minimally invasive evidence preservation. We therefore intend to introduce screen recording. No cameras, no audio, no classic proctoring – that doesn’t make sense with 300 people in a room. Just screenshots every few seconds.

Our plan naturally considers the principles of data protection:

- Transparency: Students are informed in advance according to Art. 13 GDPR – thereby deterrent effect

- Separation: Screenshots are kept separately from examination answers

- Access control: Examiners do not receive the screenshots.

- Automatic deletion after expiration of the objection period.

- Purpose limitation: Evaluation only in concrete disputes and to prevent cheating attempts (whether without cause or only cause-related is still to be clarified)

The pure existence of the recording probably prevents more attempts than we will ever document.

Is this proportionate? We think so. The screenshots only document what happens on the examination screen – not the person, not the room. They are only looked at in case of suspicion or conflict. And they are automatically deleted.

The screenshots could also be didactically valuable after grading. How do students navigate through the examination? Where do they spend most time? Which tasks are skipped? How do they revise errors?

Some colleagues would like to use such data to improve their examinations. But the legal basis? Public interest in good teaching? Consent? We are still cautious here until this is clarified in terms of data protection law.

Data protection and traceability famously form an area of tension. We can try to resolve the goal conflict between anonymity and control through technology and organizational measures as well as possible for the parties involved.

Speaking of anonymity – to conclude, I want to show how far one could drive data protection if one really wanted to…

In Short – Part 3

Minimally invasive evidence preservation: Screenshots every few seconds – no cameras, no audio, no classic proctoring.

Deterrence works: The pure existence of the recording prevents more attempts than are documented.

Privacy by design: Automatic deletion, purpose limitation, and strict access control protect privacy.

In the final part of our series, we dare to look into the future: What could genuine anonymity in examinations look like – with a surprisingly analog solution?

Article Series: AI and Privacy in E-Examinations

This is the final Part 4 of 4 of our series on e-examinations, AI, and privacy.

The complete series:

- The Foundations – psi-exam and the Goal Conflicts

- AI in Practice – Opportunities and Limits

- Control and Traceability – The Screenshot Solution

- Zero-Trust Vision – TEARS and Outlook (this article)

To conclude our series, we show how far one could drive the data protection idea: TEARS – a zero-trust system with paper slips that proves genuine anonymity in examinations is technically possible.

TEARS: Zero-Trust Grading

Let’s come to the last part, which is more academically interesting. It’s about showing how far one could drive the data protection idea. On my slide about goal conflicts, two points are still open: anonymous grading and power imbalance.

I had already hinted at the structural problem: Students find themselves in an ungrateful situation. They are at the mercy of what the university as an institution and we as examiners specify. However, it would be desirable if both parties could act on equal footing in the examination situation – after all, it’s about the students’ future.

Therefore, a provably anonymous grading would be desirable. This would mean that nobody has to rely on the goodwill or integrity of the university.

With our psi-exam system – and all e-examination systems I know that are used in practice – students must trust the university. After the exam, the answers are downloaded from the laptops by the organizer. The answers still bear the names of the test-takers at this point. Only when the data is passed on to the examiners are the names replaced by animal pseudonyms.

This mechanism presupposes that the organizer keeps their promise – i.e., doesn’t send the examiner an invitation link that reveals the actual names before completion of grading. Perhaps examiner and organizer are colleagues who work together a lot – how credible is such a promise then? If you often have lunch together or sit together at after-work drinks?

And what do we do when both roles – as with me currently – are united in one person? Then I’ll probably have to compartmentalize my thoughts better in the future… This is unsatisfying and hard to maintain in practice.

One could now retreat to the position that organizationally enforced role separation suffices – it’s simply regulated by service instruction and then everyone will certainly stick to it!

But wouldn’t it be more elegant if we could solve this technically so that no trust is necessary? It would be particularly elegant if we could solve it so that even technical laypeople could understand that the procedure establishes anonymity. One should be able to understand it without knowing how the cryptographic procedures usually required for this work.

This is a nice problem.

Anonymity Through Tearing

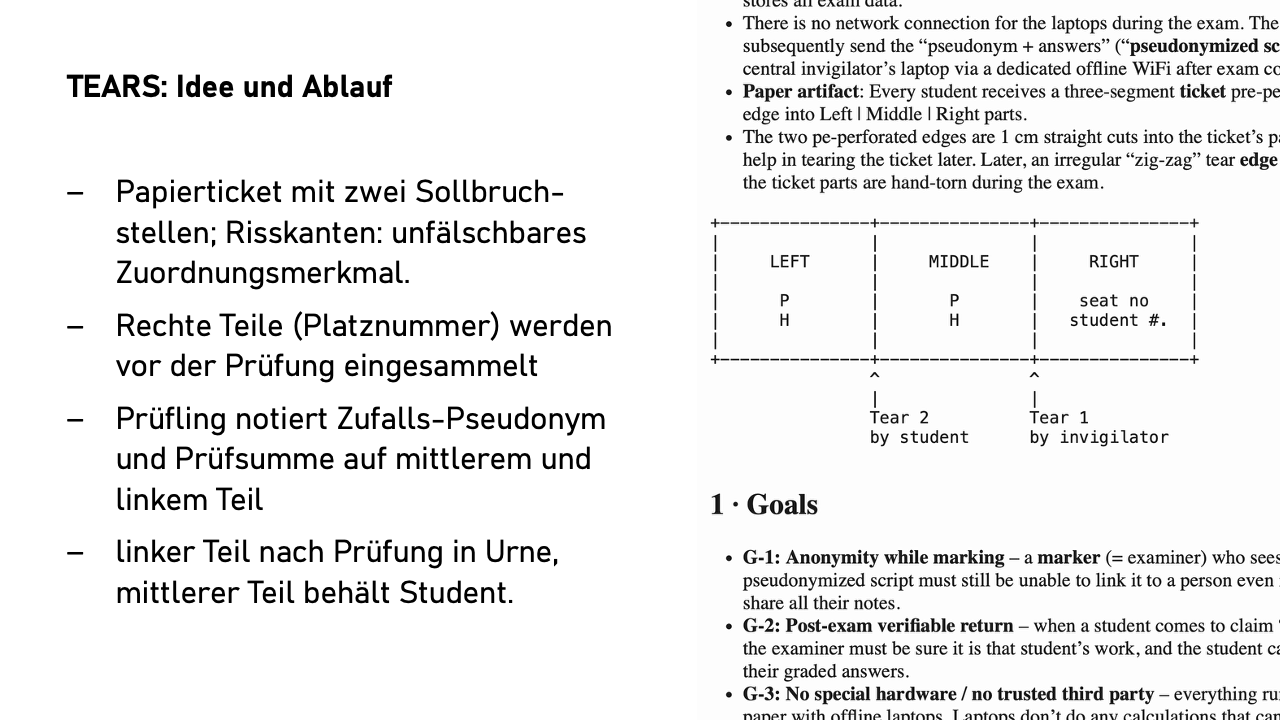

We have developed an elegant solution for this problem. It’s called TEARS – from the English “to tear.” The basic idea: Paper tears unpredictably.

Each test-taker receives a paper ticket with two predetermined breaking points that is torn into three parts during the exam. The irregular tear edges are practically unforgeable. It is impossible in practice to perfectly replicate a tear edge created during the exam at home.

At the beginning, the supervisor comes to each seat, tears off the right part of the ticket, and notes the name and seat number of the student on it. The supervisor keeps this right part – it has a tear edge that will later fit perfectly with the middle part.

At the start of the exam, each laptop shows a randomly generated pseudonym – let’s say “A37BTX.” The student writes this pseudonym on both the middle and left parts of their own ticket. Then they work normally on the exam. Test-takers do not enter their name on the laptop.

At the end of the exam, the system shows a checksum over all entered answers – a kind of digital fingerprint of the exam. The student also notes this – let’s say, ten-character – string on both remaining parts. The left part is torn off when leaving the room and thrown into an urn – a box where all left parts land unsorted. The student takes the middle part home. This part is the crucial piece of evidence – it has both tear edges and can later be matched with both the right part (with the supervisor, after the exam with the examiner) and the left part (in the urn, after the exam also with the examiner).

Grading is done completely anonymously under the pseudonym. Examiners only see “Exam A37BTX” with the corresponding answers.

For grade announcement, the student brings the middle part and says: “I am Max Müller, here is my ID.” The examiner fetches the other two parts – the right one with “Max Müller, Seat 17” and the left part matching the middle part – easily found by pseudonym and checksum – from the urn. Now comes the puzzle game: Only if all three tear edges fit together perfectly is the assignment proven and the performance is announced and recorded for the student.

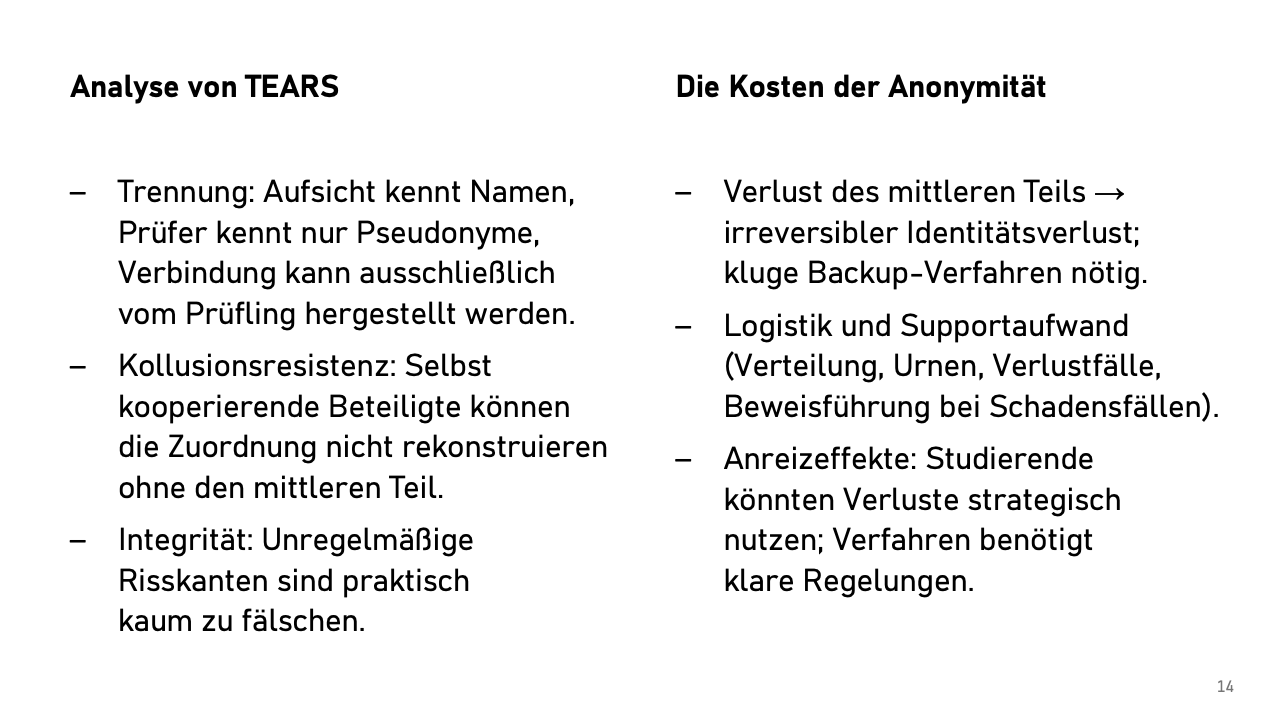

Is This Secure and Anonymous?

Security lies in the distribution of knowledge. Even if all parties worked together, they would always be missing a crucial puzzle piece.

The supervisor knows the right parts with the names and sees the left parts in the urn with the pseudonyms. But which left part belongs to which right one? This cannot be determined – the connecting middle piece is missing.

The examiners in turn only know pseudonyms and the associated examination answers, but no names. The only connection between all three parts is the middle part with its two matching tear edges – and only the students have that.

One could now object: What about forged tear edges, perhaps to get the better grade of other students? Here physics comes into play. The supervisor tears the ticket spontaneously and without preparation – simply as it comes. This random, irregular tear edge is unique. You could try at home a hundred times to replicate exactly this pattern – it will hardly succeed. And even if: The middle piece needs another perfectly matching edge to the left piece on the other side. So that has to tear perfectly again – and you only have one attempt for that – in the end, the three parts must again have exactly the format of the original ticket.

This elegant solution naturally has a catch: What happens when students lose their middle part?

If only one person loses their middle piece, that’s not yet a problem. After assigning all others, exactly one exam remains – problem solved. It becomes critical when several students lose their papers. Then theoretically any of the remaining exams could belong to any of them.

The system therefore needs a backup procedure for such cases. But here it gets tricky: The backup must not undermine anonymity, otherwise dissatisfied students would have an incentive to accidentally lose their papers to benefit from the exception rule.

We haven’t yet come up with a really convincing backup procedure. If someone has a good idea – I’m all ears!

TEARS is a thought experiment that shows: Data protection through technology can go much further than most think possible. You don’t need blockchain, no zero-knowledge proofs, no highly complex cryptography. Sometimes the analog solution is the more elegant one.

Will we implement TEARS practically? Probably not. The danger of lost papers, the organizational effort – much speaks against it.

But that’s not the point either. TEARS shows that genuine anonymity in examinations is technically possible. If a zero-trust system works with paper slips, then the argument “that just doesn’t work (better)” becomes less convincing. Often it will certainly be used as a pretext; what’s actually meant is: “We don’t want that.” That’s perfectly fine – but we should be honest about what’s technically possible and what we don’t want to implement for pragmatic reasons.

Conclusion: Where Do We Stand?

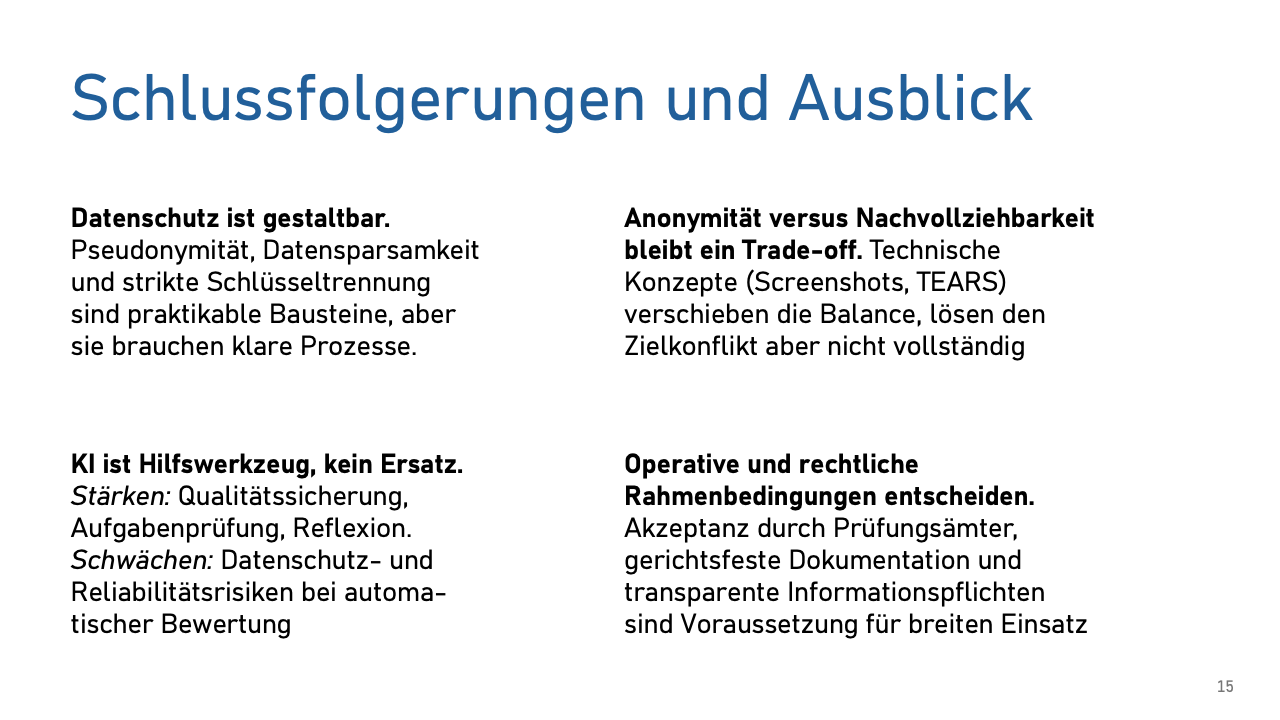

We have played through two goal conflicts here: data protection versus AI benefits, anonymity versus control. The perfect solution? Doesn’t exist. But we can shape the trade-offs so that all parties involved can live with them.

What does our experience with psi-exam show? Data protection-friendly e-examinations are possible – and without quality suffering. On the contrary: Through pseudonymous task-wise grading and the possibility of applying grading changes across examinations, equal treatment is better than with paper exams. Data minimization doesn’t have to be added on, it can be technically built in.

My position on AI is as follows: It’s not a panacea, but a tool with a clear profile. Excellent for task quality and grading dialogue, problematic for automation. The workload doesn’t decrease – it shifts. We don’t grade faster, but more thoroughly. That’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

I repeatedly hear that something is completely impossible – “Examinations on laptops without cabling – that’s not possible at all.” And then it is possible after all. This also applies to supposedly insurmountable data protection hurdles. You just have to take the time to talk to colleagues from the data protection office.

The exciting question is therefore not what is technically possible. Technology is usually much more flexible than thought. The question is: What do we want as a reasonable compromise between the desirable and the practicable? And there’s still much to explore.

In Short – The Complete Series

Privacy is shapeable: From technically enforced pseudonymity to zero-trust approaches – the possibilities are more diverse than thought.

AI is a tool, not a panacea: Quality assurance yes, automation (not yet) no.

Trade-offs remain: The perfect solution doesn’t exist, but we can consciously shape the balance.

The future is open: What is technically possible and what we want to implement pragmatically are two different questions – both deserve honest discussion.

This article series is based on my talk at the meeting of data protection officers from Bavarian universities. I’m happy to answer any questions and engage in discussion.

Appendix: Notes from the Discussion

AI as First Examiner?

Question: Could the first grading be done completely by AI and only the second examiners look over it?

Answer: Technically feasible, but probably legally and psychologically problematic. With current technology, second examiners would factually have to completely re-grade everything – that’s more work for them, not less. The psychological trap: AI evaluations always sound plausible, the temptation to adopt them unchecked is real.

Screen Recording and Data Protection

Discussion: Screen recording was intensively discussed. From a data protection perspective, it appeared implementable under the given conditions:

- Clear purpose limitation (only in disputes)

- Transparency (Art. 13 GDPR information)

- Automatic deletion after objection period

- No access for examiners, only for examination committee when needed

Alternative approaches like recording keystrokes were discussed, but this doesn’t prove everything and possibly involves biometric data (Art. 9 GDPR).

Cheating Attempts and Practical Use Cases

Illustrative examples from the discussion: A fictional example for the necessity of screenshots: A student puzzles over a task for ten minutes, scrolls the text back and forth. Then the person goes to the bathroom, comes back after seven minutes, and writes the perfect answer. What happened? A flash of inspiration in the bathroom or something else? The screenshots would document such anomalies.

Similarly, one could detect if someone gains internet access through security holes on the laptops and accesses ChatGPT during the exam. Or if someone pastes text from the clipboard (not suspicious in itself), but then the following text appears on screen: “As a large language model, I believe you should answer this task as follows” – and deletes this text from the form fields before submitting the exam.

Limitation: No live monitoring or AI evaluation of screenshots planned. This would undermine the high reliability requirements – if AI analysis fails due to power outage or network disruptions, this must not endanger the entire exam. Instead, only retrospective manual evaluation in concrete suspicion cases.

Time Management and Flexible Processing Times

Discussion about time extensions: Why doesn’t the system automatically lock editing capability when exam time has expired? My answer: Because we want to give supervisors uncomplicated full control over exam conduct. As with paper exams, supervisors should be able to react flexibly.

Practical example: We already had an emergency medical response in the examination room during the exam; immediately adjacent students received spontaneous time extensions from supervisors – without having to look up computer numbers and configure the extension in a system.

Here too, screenshots show their utility: If someone continues writing after official end, this is documented. As with paper exams, an exam can thereby be declared invalid after the end of processing time for such rule violations. Certainly debatable, but I think: It should also be possible to fail an exam for such rule violations in e-examinations.

Other Technical Solutions

Input from the audience:

- Case Train (University of Würzburg): individual time extension possible, analysis of typing behavior for cheating detection (copy-paste behavior)

- Proctorio and other US providers: Third-country transfer problems, fundamental rights interventions when using private devices

Task Types and Limitations

Question: Which task types don’t work well electronically?

Answer: Drawings, sketches, mathematical derivations with many symbols are difficult. Pragmatic solution: These parts continue on paper, then scan and merge with electronic parts. Alternative: Prepared diagrams for annotation.

Documentation and Compliance

Questions about data protection documentation: The current system has:

- Basic process documentation

- Art. 13 GDPR information for all parties involved

- Checklists for exam conduct

- Archiving concept with deletion periods

Still missing: Formal processing directory (will be created when needed). Assessment in the room: Technical documentation together with data protection basic considerations meets documentation requirements at least basically.

Remote Examinations: Less Relevant Than Thought

Experience: Despite technical possibilities, hardly any demand for remote examinations. Even Erasmus students prefer paper exams on-site abroad over proctored digital remote examinations. Is this perhaps a solution for a problem nobody has? At other universities, however, many aptitude assessment procedures run as remote examinations.

Institutional Challenges

Reality: The system currently runs as a “functional prototype” at the chair, still financed by third-party funds for the next few years, not as a university service. Transfer to regular operation will require:

- Enhancement of technical implementation for regular operation

- Dedicated personnel, training of existing administrative staff

- More comprehensive documentation

- Political will and financing

Pragmatism: “Best effort” – it works, thousands of examinations have been conducted, within the framework of the BaKuLe project the transfer to regular operation is being explored and carried out.